American Revolutionary War

Battles for 1775

The Battle of Bunker Hill

June 17, 1775 at Charlestown, Massachusetts

Battle Summary

The Battle of Bunker Hill was fought during the Siege of Boston in the early stages of the Revolutionary War.

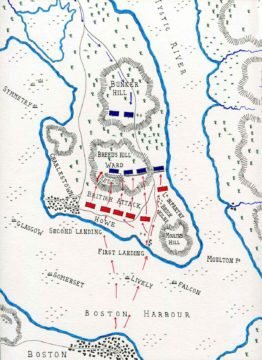

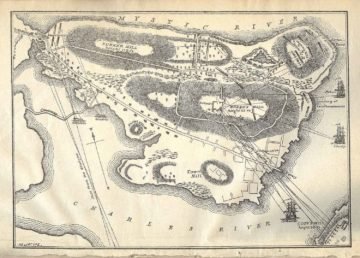

The battle is named after Bunker Hill in Charlestown, Massachusetts, which was peripherally involved in the battle. It was the original objective of both the colonial and British troops, though the majority of combat took place on the adjacent hill which later became known as Breed’s Hill.

On June 13, the leaders of the colonial forces besieging Boston learned that the British were planning to send troops out from the city to fortify the unoccupied hills surrounding the city, which would give them control of Boston Harbor. In response, 1,200 colonial troops under the command of William Prescott stealthily occupied Bunker Hill and Breed’s Hill. During the night, the colonists constructed a strong redoubt on Breed’s Hill, as well as smaller fortified lines across the Charlestown Peninsula.

On June 17, at daybreak, the British became aware of the presence of colonial forces on the Peninsula and mounted an attack against them that day. Two assaults on the colonial positions were repulsed with significant British casualties; the third and final attack carried the redoubt after the defenders ran out of ammunition. The colonists retreated to Cambridge over Bunker Hill, leaving the British in control of the Peninsula.

The battle was a tactical, though somewhat Pyrrhic victory for the British, as it proved to be a sobering experience for them, involving many more casualties than the Americans had incurred, including a large number of officers. The battle had demonstrated that inexperienced militia were able to stand up to regular army troops in battle. Subsequently, the battle discouraged the British from any further frontal attacks against well defended front lines. American casualties were comparatively much fewer, although their losses included General Joseph Warren and Major Andrew McClary, the final casualty of the battle.

The battle led the British to adopt a more cautious planning and maneuver execution in future engagements, which was evident in the subsequent New York and New Jersey campaign, and arguably helped rather than hindered the American forces. Their new approach to battle was actually giving the Americans greater opportunity to retreat if defeat was imminent. The costly engagement also convinced the British of the need to hire substantial numbers of foreign mercenaries to bolster their strength in the face of the new and formidable Continental Army.

British planning

Throughout May, in response to orders from Gage requesting support, the British received reinforcements, until they reached a strength of about 6,000 men.

On May 25, three generals arrived on HMS Cerberus: William Howe, John Burgoyne, and Henry Clinton. Gage began planning with them to break out of the city, finalizing a plan on June 12. This plan began with the taking of the Dorchester Neck, fortifying the Dorchester Heights, and then marching on the colonial forces stationed in Roxbury.

Once the southern flank had been secured, the Charlestown heights would be taken, and the forces in Cambridge driven away. The attack was set for June 18.

On June 13, the Massachusetts Provincial Congress was notified, by express messenger from the Committee of Safety in Exeter, New Hampshire, that a New Hampshire gentleman “of undoubted veracity” had, while visiting Boston, overheard the British commanders making plans to capture Dorchester and Charlestown.

On June 15, the Massachusetts Committee of Safety decided that additional defenses needed to be erected. General Ward directed General Israel Putnam to set up defenses on the Charlestown Peninsula, specifically on Bunker Hill.

Facts about the Battle of Bunker Hill

- Armies – American Forces was commanded by Col. William Prescott and consisted of about 2,400 Soldiers. British Forces was commanded by Gen. William Howe and consisted of about 3,000 Soldiers.

- Casualties – American casualties were estimated to be 115 killed, 305 wounded, and 30 captured. British casualties were estimated to be 226 killed and 828 wounded.

- Outcome – The result of the battle was a British victory. The battle was part of the Boston campaign, 1774-76.

Prelude

Fortification of Breed’s Hill

On the night of June 16, colonial Col. William Prescott led about 1,200 men onto the peninsula in order to set up positions from which artillery fire could be directed into Boston. This force was made up of men from the regiments of Prescott, Putnam (the unit was commanded by Thomas Knowlton), James Frye, and Ebenezer Bridge.

At first, Putnam, Prescott, and their engineer, Capt. Richard Gridley, disagreed as to where they should locate their defense. Some work was performed on Bunker Hill, but Breed’s Hill was closer to Boston and viewed as being more defensible. Arguably against orders, they decided to build their primary redoubt there. Prescott and his men, using Gridley’s outline, began digging a square fortification about 130 feet on a side with ditches and earthen walls. The walls of the redoubt were about 6 feet high, with a wooden platform inside on which men could stand and fire over the walls.

The works on Breed’s Hill did not go unnoticed by the British. Gen. Clinton, out on reconnaissance that night, was aware of them, and tried to convince Gage and Howe that they needed to prepare to attack the position at daylight. British sentries were also aware of the activity, but most apparently did not think it cause for alarm. Then, in the early predawn, around 4:00 AM, a sentry on board HMS Lively spotted the new fortification, and notified her captain. Lively opened fire, temporarily halting the colonists’ work.

Aboard his flagship HMS Somerset, Admiral Samuel Graves awoke, irritated by the gunfire that he had not ordered. He stopped it, only to have General Gage countermand his decision when he became fully aware of the situation in the morning. He ordered all 128 guns in the harbor, as well as batteries atop Copp’s Hill in Boston, to fire on the colonial position, which had relatively little effect. The rising sun also alerted Prescott to a significant problem with the location of the redoubt – it could easily be flanked on either side. He promptly ordered his men to begin constructing a breastwork running down the hill to the east, deciding he did not have the manpower to also build additional defenses to the west of the redoubt.

British preparations

When the British generals met to discuss their options, Clinton, who had urged an attack as early as possible, preferred an attack beginning from the Charlestown Neck that would cut off the colonists’ retreat, reducing the process of capturing the new redoubt to one of starving out its occupants. However, he was outvoted by the other three generals. Howe, who was the senior officer present and would lead the assault, was of the opinion that the hill was “open and easy of ascent and in short would be easily carried.” General Burgoyne concurred, arguing that the “untrained rabble” would be no match for their “trained troops“. Orders were then issued to prepare the expedition.

When General Gage surveyed the works from Boston with his staff, Loyalist Abijah Willard recognized his brother-in-law Colonel Prescott. “Will he fight?” asked Gage. “[A]s to his men, I cannot answer for them;” replied Willard, “but Colonel Prescott will fight you to the gates of hell.” Prescott lived up to Willard’s word, but his men were not so resolute. When the colonists suffered their first casualty, Asa Pollard of Billerica, a young private killed by cannon fire, Prescott gave orders to bury the man quickly and quietly, but a large group of men gave him a solemn funeral instead, with several deserting shortly thereafter.

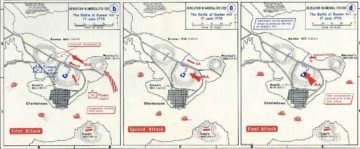

It took six hours for the British to organize an infantry force and to gather up and inspect the men on parade. General Howe was to lead the major assault, drive around the colonial left flank, and take them from the rear. Brig. Gen. Robert Pigot on the British left flank would lead the direct assault on the redoubt, and Maj. John Pitcairn led the flank or reserve force. It took several trips in longboats to transport Howe’s initial forces (consisting of about 1,500 men) to the eastern corner of the peninsula, known as Moulton’s Point.

By 2:00 PM, Howe’s chosen force had landed. However, while crossing the river, Howe noted the large number of colonial troops on top of Bunker Hill. Believing these to be reinforcements, he immediately sent a message to Gage, requesting additional troops. He then ordered some of the light infantry to take a forward position along the eastern side of the peninsula, alerting the colonists to his intended course of action. The troops then sat down to eat while they waited for the reinforcements.

Colonists reinforce their positions

Battle of Bunker Hill aka Breed’s Hill-the British Marines and Foot storm over the side of the Patriot redoubt

Prescott, seeing the British preparations, called for reinforcements. Among the reinforcements were Joseph Warren, the popular young leader of the Massachusetts Committee of Safety, and Seth Pomeroy, an aging Massachusetts militia leader. Both of these men held commissions of rank, but chose to serve as infantry. Prescott ordered the Connecticut men under Capt. Knowlton to defend the left flank, where they used a crude dirt wall as a breastwork, and topped it with fence rails and hay. They also constructed three small v-shaped trenches between this dirt wall and Prescott’s breastwork. Troops that arrived to reinforce this flank position included about 200 men from the 1st and 3rd New Hampshire regiments, under Cols. John Stark and James Reed.

Stark’s men, who did not arrive until after Howe landed his forces (and thus filled a gap in the defense that Howe could have taken advantage of, had he pressed his attack sooner), took positions along the breastwork on the northern end of the colonial position. When low tide opened a gap along the Mystic River to the north, they quickly extended the fence with a short stone wall to the water’s edge. Colonel Stark placed a stake about 100 feet in front of the fence and ordered that no one fire until the regulars passed it. Just prior to the action, further reinforcements arrived, including portions of Massachusetts regiments of Cols. Brewer, Nixon, Woodbridge, Little, and Major Moore, as well as Callender’s company of artillery.

Behind the colonial lines, confusion reigned. Many units sent toward the action stopped before crossing the Charlestown Neck from Cambridge, which was under constant fire from gun batteries to the south. Others reached Bunker Hill, but then, uncertain about where to go from there, milled around. One commentator wrote of the scene that “it appears to me there never was more confusion and less command.” While Putnam was on the scene attempting to direct affairs, unit commanders often misunderstood or disobeyed orders.

Battle Begins

British assault

By 3:00 PM, the British reinforcements, which included the 47th Foot and the 1st Marines, had arrived, and the British were ready to march. Brig. Gen. Pigot’s force, gathering just south of Charlestown village, were taking casualties from sniper fire, and Howe asked Admiral Graves for assistance in clearing out the snipers. Graves, who had planned for such a possibility, ordered incendiary shot fired into the village, and then sent a landing party to set fire to the town. The smoke billowing from Charlestown lent an almost surreal backdrop to the fighting, as the winds were such that the smoke was kept from the field of battle.

Pigot, commanding the 5th, 38th, 43rd, 47th, and 52nd regiments, as well as Major Pitcairn’s Marines, were to feint an assault on the redoubt. However, they continued to be harried by snipers in Charlestown, and Pigot, when he saw what happened to Howe’s advance, ordered a retreat.

Gen. Howe led the light infantry companies and grenadiers in the assault on the American left flank, expecting an easy effort against Stark’s recently arrived troops. His light infantry were set along the narrow beach, in column, in order to turn the far left flank of the colonial position. The grenadiers were deployed in the middle. They lined up four deep and several hundred across. As the regulars closed, John Simpson, a New Hampshire man, prematurely fired, drawing an ineffective volley of return fire from the regulars. When the regulars finally closed within range, both sides opened fire. The colonists inflicted heavy casualties on the regulars, using the fence to steady and aim their muskets, and benefit from a modicum of cover. With this devastating barrage of musket fire, the regulars retreated in disarray, and the militia held their ground.

The regulars reformed on the field and marched out again. This time, Pigot was not to feint; he was to assault the redoubt, possibly without the assistance of Howe’s force. Howe, instead of marching against Stark’s position along the beach, marched instead against Knowlton’s position along the rail fence. The outcome of the second attack was much the same as the first. One British observer wrote, “Most of our Grenadiers and Light-infantry, the moment of presenting themselves lost three-fourths, and many nine-tenths, of their men. Some had only eight or nine men a company left …” Pigot did not fare any better in his attack on the redoubt, and again ordered a retreat. Meanwhile, in the rear of the colonial forces, confusion continued to reign. Gen. Putnam tried, with only limited success, to send additional troops from Bunker Hill to Breed’s Hill to support the men in the redoubt and along the defensive lines.

The British rear was also in some disarray. Wounded soldiers that were mobile had made their way to the landing areas, and were being ferried back to Boston, and the wounded lying on the field of battle were the source of moans and cries of pain. General Howe, deciding that he would try again, sent word to Gen. Clinton in Boston for additional troops. Clinton, who had watched the first two attacks, sent about 400 men from the 2nd Marines and the 63rd Foot, and then followed himself to help rally the troops. In addition to the new reserves, he also convinced about 200 of the wounded to form up for the third attack.

During the interval between the second and third assaults, Putnam continued trying to direct troops toward the action. Some companies, and leaderless groups of men, moved toward the action; others retreated. John Chester, a Connecticut captain, seeing an entire company in retreat, ordered his company to aim muskets at that company to halt its retreat; they turned about and headed back to the battlefield.

The third assault, concentrated on the redoubt (with only a feint on the colonists’ flank), was successful, although the colonists again poured musket fire into the British ranks, and it cost the life of Major Pitcairn. The defenders had run out of ammunition, reducing the battle to close combat. The British had the advantage once they entered the redoubt, as their troops were equipped with bayonets on their muskets while most of the colonists were not. Col. Prescott, one of the last colonists to leave the redoubt, parried bayonet thrusts with his normally ceremonial sabre. It is during the retreat from the redoubt that Joseph Warren was killed.

The retreat of much of the colonial forces from the peninsula was made possible in part by the controlled retreat of the forces along the rail fence, led by John Stark and Thomas Knowlton, which prevented the encirclement of the hill. Their disciplined retreat, described by Burgoyne as “no flight; it was even covered with bravery and military skill“, was so effective that most of the wounded were saved; most of the prisoners taken by the British were mortally wounded.

Putnam attempted to reform the troops on Bunker Hill; however the flight of the colonial forces was so rapid that artillery pieces and entrenching tools had to be abandoned. The colonists suffered most of their casualties during the retreat on Bunker Hill. By 5:00 PM, the colonists had retreated over the Charlestown Neck to fortified positions in Cambridge, and the British were in control of the peninsula.

Aftermath

The British had taken the ground but at a great loss; they had suffered 1,054 casualties, with a disproportionate number of these officers. The casualty count was the highest suffered by the British in any single encounter during the entire war. Gen. Clinton, echoing Pyrrhus of Epirus, remarked in his diary that “A few more such victories would have shortly put an end to British dominion in America.”

British dead and wounded included 100 commissioned officers, a significant portion of the British officer corps in North America. Much of Gen. Howe’s field staff was among the casualties. Maj. Pitcairn had been killed, and Lt. Col. James Abercrombie fatally wounded.

The colonial losses were about 450, of whom 140 were killed. Most of the colonial losses came during the withdrawal. Maj.Andrew McClary was technically the highest ranking colonial officer to die in the battle; he was hit by cannon fire on Charlestown Neck, the last person to be killed in the battle. He was later commemorated by the dedication of Fort McClary in Kittery, Maine.

A serious loss to the Patriot cause, however, was the death of Dr. Joseph Warren. He was the President of Massachusetts’ Provincial Congress, and he had been appointed a Major General on June 14. His commission had not yet taken effect when he served as a volunteer private three days later at Bunker Hill. Only thirty men were captured by the British, most of them with grievous wounds; twenty died while held prisoner. The colonials also lost numerous shovels and other entrenching tools, as well as five out of the six cannon they had brought to the peninsula.