Battle of Lexington and Concord

The first Battle of the Revolutionary War was fought on April, 19 1775 at Lexington and Concord in Middlesex County, Massachusetts. British troops led by Lt. Col. Francis Smith were confronted by untrained militia commanded by Capt. John Parker.

| Battle of Lexington and Concord Facts | |||

|

|||

| American Forces Commanded by Capt. John Parker |

|||

| Strength | Killed | Wounded | Missing / Captured |

| 3,960 | 49 | 39 | 5 |

| British Forces Commanded by Lt. Col. Francis Smith |

|||

| Strength | Killed | Wounded | Missing / Captured |

| 1,500 | 73 | 174 | 53 |

| Outcome of Battle | |||

| Patriot Victory: British forces raiding Concord driven back into Boston with heavy losses. Part of the Boston Campaign, 1774-76 | |||

In February, the British Parliament declared the colony of Massachusetts to be in open rebellion and authorized British troops to kill the violent rebels.They were ordered to destroy all of the stores that had ammunition, rifles, or other arms.

Lt. Gen. Thomas Gage, the commander-in-chief of the British Army in America, was given command to quell the rebellion. He gave the orders to the British troops to destroy stores and rebels.

He thought that the citizens were planning to collect enough arms to form a rebellion. Some American spies learned of the British orders and sent word to the townspeople of the local areas.

Paul Revere and William Dawes were sent on different routes to warn the people about the British march to Concord.

Before he left, Revere hung 2 lanterns in the bell tower of the Old North Church, indicating that the British were coming by sea. Revere is noted as yelling the famous phrase “The Regulars are coming!”

When they arrived in Lexington, Dr. Samuel Prescott joined Revere and Dawes in order to spread the word to the townspeople.

Just after 1:00 A.M., between Lexington and Concord, Revere and Dawes ran into a British patrol. Revere was captured trying to escape and Dawes was forced away and rode back to Lexington. However, Prescott managed to finish his route to Concord.

Battle of Lexington

On April 18, during the early morning hours, Gage dispatched troops under Lt. Col. Frances Smith and Maj. James Pitcairn to seize these munitions. The British force left Boston Common and landed their boats at Phip’s Farm.

Between 11:00 P.M. and 12:00 A.M., they waded ashore and waited for 2 hours while extra provisions were landed and distributed.

On April 19, between 1:00-2:00 A.M., Smith finally got his troops marching. When they arrived at Menotomy around 3:00 A.M., Smith learned that his advance was no longer a secret. He ordered Pitcairn ahead with 6 light companies to secure the bridges at Concord.

Massachusetts militia the Minutemen turning out to oppose the British march to Concord.

The town of Lexington was a small crossroads community of 750 people. The British forces were prepared to face 500 militia. At first, there was about 170 militiamen that responded to the initial call to arms. After waiting for a while and not seeing any British forces, they were told to disperse and wait for the next call.

At around 1:00 A.M., there were only 70 out of the original 170 militiamen that constituted the American force. Capt. John Parker managed to get about 40 militiamen to line up on the town’s green. Another 30 or so militia were scattered around the Common grounds and the nearby buildings.

Around 4:30 A.M., Pitcairn neared the Lexington Common. Their guns were already primed and loaded. As the British approached Lexington, their advance guard captured 3 militia scouts that were just outside of the town, waiting to spot the British approach. The fourth militia scout, Thaddeus Brown, escaped capture and rode back into town. He warned Parker that the British were 1/2 mile away. Pitcairn was told that 500 militiamen were in town waiting for his force. He slowed his advance and waited for Smith’s force to catch up to his.

Pitcairn ordered his men to surround the disarm the local militia that had gathered, specifically ordering them not to open fire on the militia. At nearly the same time, Parker ordered his militia to disperse, which they began to do.

Pitcairn’s plan was to not get bogged down, since his orders were to peacefully take possession of the Concord bridges. However, he could not leave the militia unmolested. Meanwhile, Parker was satisfied with the show of presence by the militia, and did not want to become engaged in a skirmish with the British.

At 5:00 A.M., just as the sun was beginning to rise, Pitcairn ordered his men to double their ranks, load their muskets, and sent them into the town at a double quick march. As the first British soldiers reached the community church at the southern end of the Common Green, Pitcairn rode to the front of his troops and ordered the militiamen to lay down their arms and disperse.

First shots on Lexington Green Battle of Lexington and Concord.

Parker recognized that his 70 militiamen did not have a chance against the powerful British force and passed the word for his men to disperse. Parker told his men not to disarm but to just disperse. An unknown soldier accidentally fired a shot. This was the infamous “Shot heard ’round the World.” It was not known if it was the British or the militia that fired the shot.

The British soldiers immediately formed up in ranks fired on the militia, who were at a range of about 40 yards. Pitcairn moved among his soldiers, trying to regain order and telling his men to cease firing. The militia returned fire while they began to scatter for cover. Within a matter of minutes, the British troops made a bayonet charge and swept the militia from the Common Green.

The British had broken ranks and were about to start breaking into houses when Smith arrived. Pitcairn and Smith soon got their troops under control and re-established order. They reformed their men into columns, fired a traditional victory volley, and headed on towards Concord.

Pitcairn’s horse was hit in two places. The regulars charged forward with bayonets. Captain Parker witnessed his cousin Jonas run through. Eight Massachusetts men were killed and ten were wounded against only one British soldier of the 10th Foot wounded (his name was Johnson, according to Ensign Jeremy Lister of that regt., present at this incident.)

The eight British colonists killed, the first to die in the Revolutionary War, were John Brown, Samuel Hadley, Caleb Harrington, Jonathon Harrington, Robert Munroe, Isaac Muzzey, Asahel Porter, and Jonas Parker. Jonathon Harrington, fatally wounded by a British musket ball, managed to crawl back to his home, and he died upon his doorstep. One wounded man, Prince Estabrook, was a black slave who served in the town’s militia.

The light infantry companies under Pitcairn at the common got beyond their officers’ control. They were firing in different directions and preparing to enter private homes. Upon hearing the sounds of muskets, Colonel Smith rode forward from the grenadier column. He quickly found a drummer and ordered him to beat assembly. The grenadiers arrived shortly thereafter, and, once they were rounded up, the light infantry were then permitted to fire a victory volley, after which the column was reformed and marched towards Concord.

Battle of Concord

On April 19, The militia had marched for about a mile or so before they saw the Regulars coming. They halted and held position until the British were within 100 rods and then they turned around and marched ahead of the British back toward Concord. At 7:00 A.M., Col. James Barrett and Maj. John Buttrick, Barrett’s second-in-command, kept the Concord militia just out of reach, moving from ridge to ridge before the British. They withdrew through the town to another ridge and held a council-of-war. They decided to withdraw across the North Bridge. Barrett and his militia watched from the west side of the river as the British entered Concord. Lt. Col. Francis Smith, the commander of the British expedition, assigned the task of securing the town to the grenadiers. He sent 1 company of light infantry to secure the South Bridge and 7 companies to the North Bridge. He chose to remain with the grenadiers in the town and kept Pitcairn, his second-in-command, with him. The grenadiers peacefully went about searching for the supplies accumulated by the Massachusetts Provincial Congress for the provincial army. However, in their impatience, they did a poor job of destroying the supplies. They threw barrels of flour and musket balls into the pond where both were easily recovered by the locals the next day. Aside from 3 24-lb. cannon that were found and destroyed, the townspeople had 3 days to remove much of the supplies to other towns.

Fight for North Bridge in Battle of Lexington and Concord.

At the North Bridge, Parson was in command of 7 companies of light infantry, a total of 196 soldiers. There were about 400 provincial militia on the nearby ridge. He left 1 company on the west side of the bridge. Two more companies were placed about a 1/4 mile away, commanded by Capt. Walter Laurie. He then took the other 4 companies and marched to Barrett’s Farm to seize ammunition and supplies as ordered by Smith. When the militia began to see smoke rising from town as the grenadiers burned captured supplies, they worried that the British were going to burn the town. They decided to move into action. They held a council-of-war and decided to march back across the bridge into town to prevent its destruction. Barrett ordered the militia to not fire until fired upon by the British Regulars, then “to fire as fast as we could.” The militia began to to approach the lone company at the bridge. After a conference between the junior officers, now left in command of the situation at the North Bridge, the other 2 companies moved back to join the third at the bridge. The militia closed to within 300 yards of the North Bridge and the 3 companies of British light infantry. A messenger was sent into town to inform Smith of the situation. He returned with word that Smith was sending some reinforcements. With the militia continuing to close in, the British retreated back across the bridge to the east side. They did not have time to properly form lines of defense. The militia that was bearing down on them was commanded by Barrett. It was made up of 6 companies: 2 from Concord, and 1 each from Bedford, Lincoln, Acton and Carlisle. Individual minutemen also came from Westford, Chelmsford and Littleton. As they closed in, the British could not completely form up and then the firing started, most likely from the British. The militia returned fire. The British returned with scattered fire and began an undisciplined retreat back to Concord. Halfway back to Concord, they met Smith, leading a company of grenadiers. He was too late, so they wheeled around and marched back into Concord. The militia remained by the bridge, lining a stone wall along the road. When Parsons and his 4 light infantry companies returned from Barrett’s farm, they were unmolested by the militia and were startled by the sight of the dead and wounded still left at the bridge. Smith remained in Concord for another 2 hours. Unaware of the events back in Concord, Parason had taken his time returning from Barrett’s Farm. The provincials did nothing except to find themselves something to eat. Barrett did not even call his officers together for consultation. Smith probably delayed in Concord in hopes of having the reinforcements that he had requested hours before reach him before he had to begin the march back.

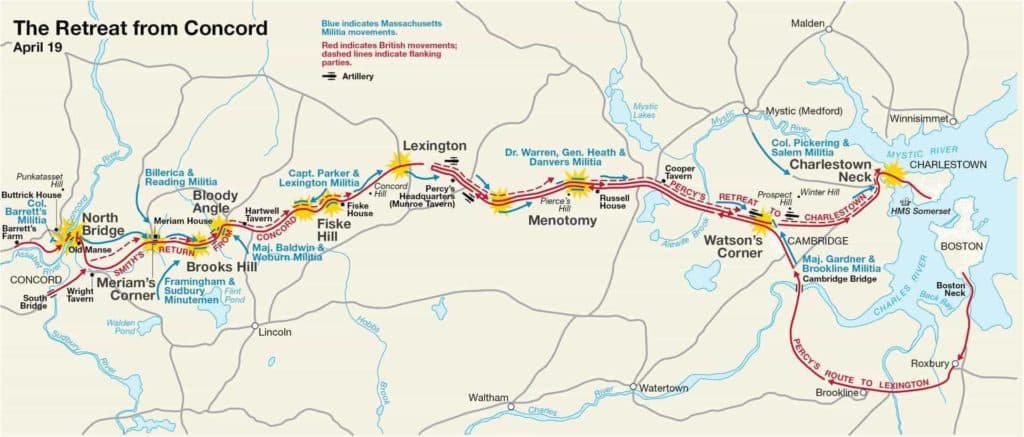

Around noon, Smith and the British made final preparations for a return march. The wounded were taken to local doctors, since there wasn’t any army surgeons that had accompanied the expedition. The walking wounded lined up in the middle of the columns and some 4 hours after they entered the town, they set out from Concord. The militia that had been at the North Bridge as well as another hundred that had turned out from nearby towns had congregated at Meriam’s Corner where the Lexington and Bedford roads forked. They fired upon the British column as it crossed a narrow bridge nearby. This began an incessant fire on the British force that continued along the entire route. As they neared Lexington, the British were running out of ammunition and just plain running in some instances. Morale and discipline were all but gone. Then a cannonball crashed into the Lexington meetinghouse. Lord Percy was on the Boston side of the Common with the reinforcements. Through a set of staff errors, the reinforcements had not left Boston until after 9:00 A.M., even though Lt. Gen. Thomas Gage had issued the orders at 4:00 A.M. It was about 2:30 P.M. when Percy’s relief force made contact with Smith’s expedition at Lexington Common, where hostilities had begun 8 hours earlier.. Percy used his field artillery to keep the militia at a distance while the wounded were tended to and Smith’s men were given a rest. At approximately 3:45 P.M., the entire British force was ready to get under way.

Maj. Gen. William Heath had arrived to assume command of the provincial forces. Dr. Joseph Warren, the Boston local that had sent William Dawes and Paul Revere to warn the countryside the night before, also arrived with Heath to join the militia at Lexington. Warren had received word of firing at Lexington Common 8 hours before. He had followed Percy’s force to Menotomy where he joined the Committee of Public Safety. Flanking parties and occasional cannon fire by the British Regulars were sometimes effective in reducing the militia firing. At 8:00 P.M., four hours after leaving Lexington, Percy’s force reached Charlestown, having endured the militia firing upon them nearly the entire route. Once in Charlestown, they were protected by the ships anchored in Boston Harbor. While the British reached the safety of Boston that evening, they would not leave again until they evacuated the city a year later. A ring of nearly 6,000 militia and American minutemen began to turn out to encircle the city and the Siege of Boston had begun. On April 20, Warren set up a headquarters in Cambridge and took control of the political aspects of the events of the previous day. Gen. Artemas Ward took military command of the militia companies surrounding Boston. The colonists were stunned by their success. No one had actually believed each side would shoot and kill each other. Some advanced; many more retreated; and some went home to see to the safety of their homes and families. Colonel Barrett eventually began to recover control and chose to divide his forces. He moved the militia back to the hilltop 300 yards away and sent Major Buttrick with the Minutemen across the bridge to a defensive position on a hill behind a stone wall. Smith, leader of the British expedition, heard the exchange of fire from his position in the town moments after he had received a request for reinforcements from Laurie. Smith assembled two companies of grenadiers to lead towards the North Bridge himself. As these troops marched, they met the shattered remnants of the three light infantry companies running towards them. Smith was concerned about the four companies which had been at Barrett’s. Their route to return safely was now gone. Then he saw the Minutemen in the distance behind their wall, and he halted his two companies and moved forward with only his officers to take a closer look. In the written words of a Minuteman behind that wall: “If we had fired, I believe we could have killed all most every officer there was in the front, but we had no orders to fire and there wasn’t a gun fired.” During this tense standoff of about 10 minutes, a mentally ill local man wandered through both sides selling hard cider. Smith returned his grenadiers to the town and hoped for the best for the remaining four companies. These men, unaware of what had happened, marched back from their fruitless search of Barrett’s farm. They passed unharmed by Barrett’s militia on the muster field and through the tiny battlefield, saw dead and wounded comrades lying on the bridge, including one who looked to them as if he had been scalped, which angered and shocked the British soldiers. They then passed sullenly over the bridge, unharmed by Buttrick’s Minutemen. The regulars all returned to the town by 10:30 a.m. Even after a small skirmish, and with superior forces, the British colonists still did not fire yet unless fired upon, and this time the regulars did nothing to provoke them. The British Army continued to destroy colonial military supplies in the town, ate lunch, reassembled for marching, then left Concord after noon.