American Revolutionary War

Battles for 1776

The Battle of Trenton

December 26, 1776 at Trenton, New Jersey

Battle Summary

After General George Washington‘s crossing of the Delaware River north of Trenton the previous night, Washington led the main body of the Continental Army against Hessian soldiers garrisoned at Trenton. After a brief battle, nearly the entire Hessian force was captured, with negligible losses to the Americans. The battle significantly boosted the Continental Army’s flagging morale, and inspired re-enlistments.

The Continental Army had previously suffered several defeats in New York and had been forced to retreat through New Jersey to Pennsylvania. Morale in the army was low; to end the year on a positive note, Washington, Commander-in-Chief of the Continental Army, devised a plan to cross the Delaware River on the night of December 25–26 and surround the Hessian garrison.

Because the river was icy and the weather severe, the crossing proved dangerous. Two detachments were unable to cross the river, leaving Washington with only 2,400 men under his command in the assault, 3,000 less than planned. The army marched 9 miles south to Trenton.

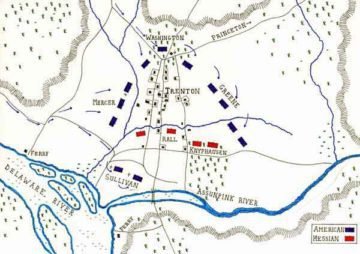

Washington had planned on a tree-pronged attack against Trenton. Major General Nathanael Greene’s division from the north, and Major General John Sullivan’s division from the west. A third division never made it across the river because of the weather but was supposed to attack from the south.

The American victory was aided by John Honeyman, a spy enlisted by Washington, who gathered intelligence in Trenton and misled the Hessian defenders. He was responsible for estimating the strength of the Hessian defenders and for convincing them that the Americans were confused and in no condition to attack. Also, the weather made crossing of the Delaware next to impossible, further enhancing the element of surprise. The Hessians sent out a patrol every night to check for nearby enemy forces, but they were not sent out that night because of the storm.

The Hessians had lowered their guard, thinking they were safe from the American army, and had no long-distance outposts or patrols. Washington’s forces caught them off guard and, after a short but fierce resistance, most of the Hessians surrendered. Almost two thirds of the 1,500-man garrison was captured, and only a few troops escaped across Assunpink Creek.

Despite the battle’s small numbers, the American victory inspired rebels in the colonies. With the success of the revolution in doubt a week earlier, the army had seemed on the verge of collapse. The dramatic victory inspired soldiers to serve longer and attracted new recruits to the ranks.

Facts about the Battle of Trenton

- Armies – American Forces was commanded by Gen. George Washington and consisted of about 2,400 Soldiers. British Forces was commanded by Col. Johann Rall and consisted of about 1,400 Soldiers.

- Casualties – American casualties were estimated to be 4 wounded. British casualties was approximately 22 killed, 92 wounded, and 948 captured.

- Outcome – The result of the battle was an American victory. The battle was part of the New York and New Jersey 1776-77 campaign.

Prelude

Washington first wanted to attack the Hessians at Bordentown, but the local militia in that area was too weak to offer support. He then chose Colonel Johann Hall’s isolated Hessian garrison at Trenton. They were in an exposed position, and it was known that they would heartily celebrate Christmas on the night of December 25. Washington decided on a predawn attack on December 26, while the Heissan troops and officers would be drunk and tired, and hopefully suffering hangovers.

On December 14, the Hessians arrived in Trenton to establish their winter quarters. Col. Carl von Donop, who despised Col. Rall, was reluctant to give command of Trenton to him. Rall was known to be loud and unacquainted with the English language, but he was also a 36-year soldier with a great deal of battle experience. His request for reinforcements had been turned down by General James Grant, who disdained the Americans and thought them poor soldiers.

Trenton lacked city walls or fortifications, which was typical of American settlements. Some Hessian officers advised Rall to fortify the town, and two of his engineers advised that a redoubt be constructed at the upper end of town, and fortifications be built along the river. The engineers went so far as to draw up plans, but Rall disagreed with them. When he was again urged to fortify the town, he replied, “Let them come … We will go at them with the bayonet.”

Loyalists came to Trenton to report the Americans were planning action. American deserters told the Hessians that rations were being prepared for an advance across the river. Rall publicly dismissed such talk as nonsense, but privately in letters to his superiors, he said he was worried about an imminent attack. He wrote to Donop that he was “liable to be attacked at any moment“. Rall said that Trenton was “indefensible” and asked that British troops establish a garrison in Maidenhead. Close to Trenton, this would help defend the roads from Americans. His request was denied.As the Americans disrupted Hessian supply lines, the officers started to share Rall’s fears.

On December 22, a spy reported to Grant that Washington had called a council of war; Grant told Rall to “be on your guard“. The main Hessian force of 1,500 men was divided into three regiments: Knyphausen, Lossberg and Rall. That night, they did not send out any patrols because of the severe weather.

Before Washington and his troops left, Benjamin Rush came to cheer up the him. While he was there, he saw a note Washington had written, saying, “Victory or Death“. Those words would be the password for the surprise attack. Each soldier carried 60 rounds of ammunition, and three days of rations.

When the army arrived at the shores of the Delaware, they were already behind schedule, and it began to rain. As the temperature dropped, the rain changed to sleet, and then to snow. The Americans began to cross the river with the soldiers crossing in Durham boats, while the horses and artillery went across on large ferries.

Two small detachments of infantry of about 40 men each were ordered ahead of main columns. They set roadblocks ahead of the main army, and were to take prisoner whoever came into or left the town. One of the groups was sent north of Trenton, and the other was sent to block River Road, which ran along the Delaware River to Trenton.

On December 26, the terrible weather conditions delayed the landings until 3:00 AM; the plan was that they were supposed to be completed by 12:00 AM. Washington realized it would be impossible to launch a pre-dawn attack. Another setback occurred for the Americans, as Brigadier Generals Cadwalader and Ewing were unable to join the attack due to the weather conditions.

At 4:00 AM, the soldiers began to march towards Trenton. Along the way, several civilians joined as volunteers, and led as guides because of their knowledge of the terrain. After marching 1.5 miles through winding roads into the wind, they reached Bear Tavern, where they turned right. They began to make better time.

They soon reached Jacobs Creek.The two groups stayed together until they reached Birmingham, where they split apart. Soon after, they reached the house of Benjamin Moore, where the family offered food and drink to Washington. At this point, the first signs of daylight began to appear. Many of the troops did not have boots, so they were forced to wear rags around their feet. Some of the men’s feet bled, turning the snow to a dark red.

As they marched, Washington rode up and down the line, encouraging the men to continue. Sullivan sent a courier to tell Washington that the weather was wetting his men’s gunpowder. Washington responded, “Tell General Sullivan to use the bayonet. I am resolved to take Trenton.”

About two miles outside of Trenton, the main columns reunited with the advance parties. They were startled by the sudden appearance of 50 armed men, but they were American. Led by Adam Stephen, they had not known about the plan to attack Trenton, and had attacked a Hessian outpost. Washington feared the Hessians would have been put on guard, and shouted at Stephen, “You sir! You Sir, may have ruined all my plans by having them put on their guard.”

Battle Begins

On December 26, at 3:00 AM, the crossing was complete but the column was not ready to march until 4:00 AM, well behind schedule. Even with intelligence from Loyalists and American deserters, having told him the day and hour of the attack, Rall did not know how large the American attacking force would be. He figured that it would be nothing more than small hit-and-run patrol actions to which he had become accustomed and indifferent.

At 4:00 AM, about four miles from their crossing at Birmingham, Washington’s force split into two columns. Greene, along with Washington, led one column onto the Pennington Road to attack the Hessian garrison from the north. Sullivan led the second column continued on the river road so it could attack the Hessian garrison from the west.

By 6:00 AM, the troops were miserable. Sullivan sent word that the men’s muskets would not fire due to being exposed to the storm all night. Washington sent word back for the men to use their bayonets instead.

At the Hessian garrison, Rall had passed out and was sound asleep along with most of his 1,200 man force, which was divided into 3 regiments: under himself, Colonel Thaddeus Knyphausen, and Colonel Lossberg. Because of the severe snowstorm, Major Dechow decided not to send out the normal predawn patrol to sweep the area for signs of the Americans. Though the storm cause extreme misery for the troops, it allowed them to approach undetected.

At 8:00 A.M., Washington’s party asked a man that was chopping wood where the Hessian sentries were, just outside of Trenton. He pointed to a nearby house. A 50-man outpost of Lt. Andreas Wiederhold saw the Americans emerge from the woods about 1/2 mile from the northern end of Trenton, on the Pennington Road.

The outpost waited until the Americans were within range, then fired an ineffective volley at them. The Americans fired three volleys and the Hessians returned one of their own. Washington ordered Edward Hand’s Pennsylvania Riflemen and a battalion of German-speaking infantry to block the road that led to Princeton.

They attacked the Hessian outpost there. Wiederholdt soon realized that this was more than a raiding party; seeing other Hessians retreating from the outpost, he led his men to do the same. Both Hessian detachments made organized retreats, firing as they fell back.

They quickly dropped back onto their main company position, some 400 yards closer to the town. About 3 minutes after this engagement, Sullivan’s advance guard flushed and routed a 50-man Hessian outpost stationed on the river road, about 1/2 mile from Trenton. Moving quickly and driving in the pickets, both columns move in on Trenton.

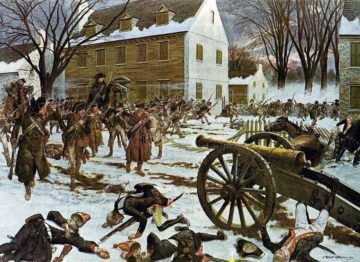

The Hessians were caught completely by surprise and were unprepared. They turned out quickly and formed up, but their attempts to attack to the north were hampered by the flanking fire from Washington’s western column and artillery. The Americans positioned two cannon on a rise that guarded the two main routes out of town. The Hessians tried to bring 4 guns into action, but the American fire kept them silent. Hamilton’s men charged down the streets after the British guns.

Knyphausen’s regiment was separated from the other two regiments and driven back through the southern end of Trenton by Sullivan’s column. Many of the Hessians were able to escape to the south across Assumpink Creek, where Ewing’s troops were supposed to have been located. Rall and Von Lossberg’s regiments were forced out of town and formed in an apple orchard at the southeast corner of town. Rall ordered a counterattack back into town, trying to force a hole to the road to Princeton. A few seconds later, Rall was hit and mortally wounded while on his horse and fell off.

The Hessians had wet guns from the storm, and had a hard time firing them. When the Hessians arrived back into Trenton’s streets, the American troops, joined by some civilians from the town, fired at them from buildings and from behind trees and fences, causing confusion. At the same time, the American cannons broke up any formations and the Hessian resistance faltered.

They retreated back to the apple orchard and tried to escape across the Assumpink Creek. There, they found the bridge blocked and the fords upstream covered by the Americans. They were soon surrounded by the fast moving Americans and left them with no choice but to surrender.

The remnants of the Knyphausen Regiment were making for Bordentown, but they were slowed down when they tried to haul their cannon through boggy ground. They soon found themselves surrounded by Sullivan’s men and they also were forced to surrender.

At 9:30 AM, the fighting finally died down. The battle had been an overwhelming victory for Washington, lasting only 90 minutes. The Americans captured 1,000 arms, several cannon and ammunition, and some much needed supplies. About 600 Hessians, most of which had been stationed on the south side of the Creek, managed to escape. This made Washington’s plan to continue towards Princeton and Brunswick out of the question. With a large body of prisoners to evacuate, and British reinforcements nearby, his own troops exhausted, and no adequate supply from across the river, Washington had no choice but to withdraw.

By noon, Washington’s force had moved to recross the Delaware back into Pennsylvania, taking their prisoners and captured supplies with them. This battle gave the Continental Congress a new confidence because it proved American forces could defeat regulars. It also increased the re-enlistments in the Continental Army forces.

The Americans had now proved themselves against a disciplined European army and the fear the Hessians inspired earlier that year in New York was broken. As Captain Johann Ewald [of the Jägers], who was with von Donop in Mt. Holly at the time of the attack, said of the Americans later, “We must now give them the honor of fortifications”.

Aftermath

Washington had turned the tide, chasing the British forces from the Delaware River and putting them on the defensive, if only for a few days. When the Continental Congress heard of Washington’s victory at Trenton, they had renewed confidence in him and it bolstered enlistments and re-enlistments for 1777. After the Hessians’ surrender, Washington is reported to have shaken the hand of a young officer and said, “This is a glorious day for our country.”

On December 28, Washington interviewed Lt. Andreas Wiederhold, who detailed the failures of Rall’s preparation. Washington soon learned however that Cadwalader and Ewing had been unable to complete their crossing, leaving his 2,400 men isolated. Without their additional 2,600 men, Washington realized he did not have the forces to attack Princeton and New Brunswick.

This small but decisive battle had an effect disproportionate to its size. The Patriot effort was galvanized, and the Americans overturned the psychological dominance achieved by the British troops in the previous months. Howe was stunned that the Patriots so easily surprised and overwhelmed the Hessian garrison.

On the contrary, Fischer argues that the changing attitudes were buoyed more by writings of Thomas Paine and additional successful actions by the New Jersey Militia than they were by the Battle of Trenton.