The Battle of Long Island

August 27 , 1776 at Long Island, New York

The Battle of Long Island (aka Battle of Brooklyn and the Battle of Brooklyn Heights) was the first major battle of the war to take place after the United States declared its independence on July 4, 1776. It was a victory for the British and the beginning of a successful campaign that gave them control of the strategically important city of New York. In terms of troop deployment and fighting, it was the largest battle of the entire war.

After defeating the British in the Siege of Boston on March 17, 1776, General George Washington brought the Continental Army to defend the port city of New York, then limited to the southern end of Manhattan Island. Washington understood that the city's harbor would provide an excellent base for the British Navy during the campaign, so he established defenses there and waited for the British to attack.

In July, the British, under the command of General William Howe, landed a few miles across the harbor from Manhattan on Staten Island. They were slowly reinforced by ships in Lower New York Bay during the next month and a half, bringing their total force to 32,000 troops. Washington knew the difficulty in holding the city with the British fleet in control of the entrance to the harbor at the Narrows. He moved the bulk of his forces to Manhattan, believing that it would be the first target.

On August 22, the British landed on the shores of Gravesend Bay.

On August 27, the British attacked American defenses on the Guan Heights. Unknown to the Patriots, however, Howe had brought his main army around their rear and attacked their flank soon after.

The Patriots panicked, resulting in 20% losses through casualties and captures, although a stand by 400 Maryland troops prevented a larger portion of the army from being lost. The remainder of the army retreated to the main defenses on Brooklyn Heights.

On the night of August 29, while the British were digging in for a siege, Gen. Washington evacuated the entire army to Manhattan without the loss of supplies or a single life. Washington and the Continental Army were driven out of New York entirely after several more defeats and forced to retreat through New Jersey and into Pennsylvania.

Facts about the Battle of Long Island

- Armies - American Forces was commanded by Gen. George Washington and consisted of 19,000 Soldiers. British Forces was commanded by Lt. Gen. William Howe and consisted of 22,000 Soldiers.

- Casualties - American casualties were estimated to be 300 killed, 650 wounded, and about 1,100 captured/missing. British casualties was approximately 63 killed, 314 wounded and unknown captured/missing.

- Outcome - The result of the battle was a British victory. The battle was part of the New York and New Jersey Campaigns 1776-77.

Prelude

On August 23, a sharp skirmish occured between the British and the Patriot advance guard about 4 miles inland at Flatbush.

On August 24, Gen. Sullivan was replaced by Major General Israel Putnam. Unfortunately, he knew little about the terrain of Long Island. Being in charge of the island's defenses, this would come back to haunt the Patriots in the coming battle.

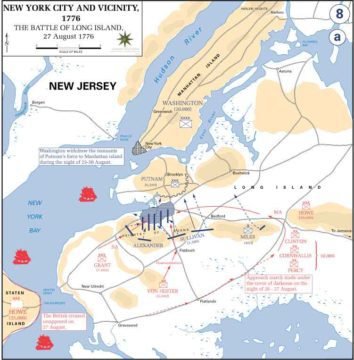

Putnam was tasked with overseeing two defensive lines perpendicular to one another. The main line contained about 6,500 troops and were deployed around Brooklyn and faced southeast. This line ran north for 1.5 miles from the mill dam-Gowanus Creek area that emptied into Gowanus Bay to Wallabout Bay. The remaining 3,000 troops were deployed to guard four strategic passes cut by major roads leading to the top and beyond the heights.

About 550 troops were on the far left guarding Gowanus Road overlooking Gowanus Bay. About 1.5 miles to the east were 1,100 troops guarding Flatbush Pass. Farther east for one mile were 800 troops guarding Bedford Pass. Still farther east of the left flank of Putnam's line were 500 riflemen. Their job was picketing a small line stretching toward Howard's Tavern at Jamacia Pass.

On August 25, additional British troops landed southeast of Denyse's Point. This brought the total number of British on Long Island to 20,000 men. Howe then split his force into two 10,000-man wings.

On August 26, in the evening, Lieutenant General Leopold P. von Heister took post at Flatbush with his Hessian force. In the following night, the larger part of the British army, commanded by General Henry Clinton, marched to gain the road leading round the easterly end of the hills to Jamaica, and to turn the left of the Americans.

Clinton arrived about two hours before day, within half a mile of this road. One of his parties fell in with a patrol of Patriot officers, and took them all prisoners, which prevented the early transmission of intelligence. Upon the first appearance of day, Clinton advanced and took possession of the heights over which the road passed. Brigadier General James Grant, with the left wing, advanced along the coast by the west road, near the narrows; but this was intended chiefly as a feint.

The guard which was stationed at this road, fled without making any resistance. A few of them were afterwards rallied, and Brigadier General William Alexander (Lord Stirling) advanced with 1,500 men. He took possession of a hill about two miles from the Patriot camp, and in front of Grant.

Howe was finally in position and ready to launch his offensive against the Patriots. Howe's plan was to send Grant to the American far right flank above Gowanus Bay to divert attention to the western end of the line. In conjunction with Grant, General von Heister would move against and hold in place the Patriot center around Flatbush. While the Patriots focused their attention on their center-right, Howe would march east and then north with 10,000 troops beyond and behind Gen. Putnam's left flank. Howe would then roll up and crush the Patriots strung out along the high ridge.

The Battle Begins

On August 27, just after midnight, Grant led his 5,000-man column north along the Gowanus Road and began skirmishing with the Patriots.

At 3:00 A.M., Putnam was told of the British movement and he ordered Alexander to advance to the far right with reinforcements. Alexander deployed about 1,600 troops to meet Grant's troops. Grant stopped in front of the Patriot line and began firing his artillery. Meanwhile, Gen. Sullivan had reached the center of the line near Flatbush Pass, where he found Gen. von Heister's Hessians firing artillery. Sullivan sent troops west to reinforce Alexander.

At 8:00 A.M., Washington arrived on Long Island. When the British attacked the Patriot right and center, Colonel Samuel Miles moved west toward the attacking British. This left the Jamacia Pass without any defenders. Learning that the pass was not defended anymore, Miles was ordered back. He arrived just in time to spot the tail end of Howe's column of baggage trains moving through the pass. Realizing the dangerous situation, Miles sent half of his men (250 troops) toward the main line to warn them and escape. With the other 250 troops, Miles attacked the baggage train. Almost all of them were captured, including Miles.

At 8:30 A.M., the British turning column reached Bedford. They had managed to march completely undetected behind Putnam's line.

At 9:00 A.M., Howe fired a pair of signal guns to alert Grant and von Heister to attack the front of the heights while Howe advanced against the rear. Unfortunately for Howe, only von Heister made their attack. He moved north up the main road in the middle of the battlefield. He ran into Sullivan's troops and attacked them. Within a few minutes, the Patriot line unraveled as the troops fled to the main Brooklyn line. Sullivan organized many of his men and made a defensive stand at Baker's Tavern. They were soon captured by von Heister's Hessians.

By 11:30 AM, Alexander's troops were overwhelmed by Grant's superior numbers. Grant had moved forward in a decisive attack that broke apart the Patriot line. Most of the Patriots tried to escape and fled toward Gowanus Creek. When Alexander learned that General Charles Cornwallis was blocking his retreat, Alexander launched a series of counterattacks with about 250 Maryland troops, commanded by Major Mordecai Gist. Unable to clear a large enough path, most of the Patriots, including Alexander, was captured.

After sweeping Putnam's troops off the Brooklyn Heights high ground, Howe's senior commanders wanted to continue their advance and attack the last line of Patriot defenses. Instead, Howe halted his troops, reorganized his command, and ordered entrenchments dug facing the Patriot defensive works. With control of the East River, he believed that Washington was trapped and had nowhere to go.

On August 28, severe rain storms prevented any fighting between Washington and Howe. Both sides stayed in place. Also, because of the high winds, Howe was unable to move his warships behind Washington's position.

On August 29, during the evening, Washington called a council-of-war to consult on the proper measures to be taken. It was determined that moving across the river was the only way to escape. He ordered that all boats that could be found to be gathered up. The plan was to use the boats to ferry his troops across the river to safety. This way, they could escape the British trap and withdraw undetected from Brooklyn Heights. A heavy rain and fog kept the Patriot escape from being seen from Howe. Heavy winds continued to keep the British ships from advancing to Washington's position.

The withdrawal started soon after it was dark from two points, the upper and lower ferries, on the East River. The intention of evacuating the island had been so prudently concealed from the troops that they did not know where they were going. The field artillery, tents, baggage, and about 9,000 men were conveyed over East River, more than a mile wide, in less than 13 hours. Being only 600 yards away, Howe and the British army had no knowledge of the Patriot withdrawal that was proceeding.

On August 30, around 6:00 AM, the last of the Patriots left the shore of Long island. The withdrawal had worked without the British finding out.

At 11:00 AM, the heavy winds finally died down enough for the British warships to begin to move upriver.

At 11:30 AM, the fog lifted. Howe ordered his troops to advance and take the Patriot works. When they arrived, they discovered that the Patriots were nowhere to be seen. Howe realized that he had let Washington and the Patriots slip through his grasp. The British warships were finally able to move upriver, just a few hours too late to stop the Patriots. If Howe could have captured Washington and his troops, this would have effectively ended the war.

Aftermath

Western Long Island

On September 11, the British received a delegation of Americans consisting of Benjamin Franklin, Edward Rutledge, and John Adams at the Conference House on the southwestern tip of Staten Island (known today as Tottenville) on the former estate of loyalist Christopher Billop. The peace conference failed as the Americans refused to revoke the Declaration of Independence. The terms were formally rejected on September 15.

On September 15, after heavily bombarding green Patriot militia forces, the British crossed to Manhattan, landing at Kip's Bay, and routed the Americans there as well. The following day, the two armies battled at Harlem Heights, resulting in a tactical draw. After a further battle at White Plains, Washington retreated across the Hudson to New Jersey. The British occupied New York until 1783, when they evacuated the city as agreed in the Treaty of Paris,.

Eastern Long Island

While most of the battle was concentrated in western Long Island, within about 10 miles of Manhattan, British troops were also deployed to the east to capture the entire 110 mile length of Long Island to Montauk. The British met little or no opposition in this operation.

Henry B. Livingston was dispatched with 200 Continental troops to draw a line at what is now Shinnecock Canal at Hampton Bays to prevent the port of Sag Harbor from falling. Livingston, faced with insufficient manpower, abandoned Long Island to the British in September.

Residents of eastern Long Island were told to take a loyalty oath to the British government. In Sag Harbor, families met on September 14, to discuss the matter at the Sag Harbor Meeting House; 14 of the 35 families decided to evacuate to Connecticut.

The British planned to use Long Island as a staging ground for a new invasion of New England. They attempted to regulate ships going into Long Island Sound and blockaded Connecticut.