The American Revolutionary War, also known as the American War of Independence, was a war between the Kingdom of Great Britain and thirteen British colonies in North American from 1775 to 1783.

The war was the end result of the political American Revolution, where the colonists overthrew British rule. In 1775, Revolutionaries seized control of all the thirteen colonial governments, established the Second Continental Congress, and created a Continental Army.

A year later, they officially declared their independence as a new country, the United States of America. From 1778 forward, other European powers would fight on the American side in the war. At the same time, Native Americans and African Americans served on both sides.

Throughout the war, the British were able to use their naval superiority to capture and occupy coastal cities, but control of the countryside (where 90% of the population lived) largely eluded them due to their relatively small land army.

In early 1778, shortly after an American victory at Saratoga, France entered the war against Britain; Spain and the Netherlands joined as allies of France over the next two years. French involvement proved decisive, with a French naval victory in the Chesapeake leading to the surrender of a British army at Yorktown in 1781.

The Treaty of Paris in 1783 ended the war and recognized the sovereignty of the United States over the territory bounded by what is now Canada to the north, Florida to the south, and the Mississippi River to the west.

The war of American independence could be summed up as a civil war fought on foreign soil, as opposing forces comprised both nations’ residents. That said, it is a war that America could not have survived without French assistance.

In addition, Britain had significant military disadvantages. Distance was a major problem: most troops and supplies had to be shipped across the Atlantic Ocean. The British usually had logistical problems whenever they operated away from port cities, while the Americans had local sources of manpower and food and were more familiar with (and acclimated to) the territory.

Additionally, ocean travel meant that British communications were always about two months out of date: by the time British generals in America received their orders from London, the military situation had usually changed.

Suppressing a rebellion in America also posed other problems. Since the colonies covered a large area and had not been united before the war, there was no central area of strategic importance. In Europe, the capture of a capital often meant the end of a war; in America, when the British seized cities such as New York and Philadelphia, the war continued unabated.

Furthermore, the large size of the colonies meant that the British lacked the manpower to control them by force. Once any area had been occupied, troops had to be kept there or the Revolutionaries would regain control, and these troops were thus unavailable for further offensive operations.

The British had sufficient troops to defeat the Americans on the battlefield but not enough to simultaneously occupy the colonies. This manpower shortage became critical after French and Spanish entry into the war, because British troops had to be dispersed in several theaters, where previously they had been concentrated in America.

The British also had the difficult task of fighting the war while simultaneously retaining the allegiance of Loyalists. Loyalist support was important, since the goal of the war was to keep the colonies in the British Empire, but this imposed numerous military limitations.

Early in the war, the Howe brothers served as peace commissioners while simultaneously conducting the war effort, a dual role which may have limited their effectiveness. Additionally, the British could have recruited more slaves and Native Americans to fight the war, but this would have alienated many Loyalists, even more so than the controversial hiring of German mercenaries.

The need to retain Loyalist allegiance also meant that the British were unable to use the harsh methods of suppressing rebellion they employed in Ireland and Scotland. Even with these limitations, many potentially neutral colonists were nonetheless driven into the ranks of the Revolutionaries because of the war.

This combination of factors led ultimately to the downfall of British rule in America and the rise of the revolutionaries’ own independent nation, the United States of America.

Which document ended the american revolutionary war?

How Long did the Revolutionary War last?

When was the Revolutionary War?

Statistical Facts of the American Revolution

General Facts

- Population (1760)…….. 1,600,000

- Population (1780)…….. 2,780,000

- Enrolled………………….. 200,000

- Ratio………………………. 5.7%

- Cost of war (1782)…….. $134,645,177

- National debt (1783)…. $36,500,375

1780 Population Estimates by State

- Pennsylvania – 327,305

- North Carolina – 270,133

- Massachusetts – 268,627

- Maryland – 245,474

- New York – 210,541

- Connecticut – 206,701

- South Carolina – 180,000

- New Jersey – 139,627

- New Hampshire – 87,802

- Delaware – 45,385

- Georgia – 56,071

- Rhode Island – 52,946

- Kentucky – 45,000

- Maine – 49,133

- Vermont – 47,620

- Tennessee – 10,000

American Battle Casualties

- Army – 4,044

- Navy – 342

- Marines – 49

- Total Deaths = 4,435

- Army – 6,004

- Navy – 114

- Marines – 70

- Total Wounded = 6,188

- Ratio – 2.4%

- Ratio-killed – 2.2%

- Ratio-dead – 2.2%

- Ratio-casualties – 5.3%

- K.I.A per Month – 55

- Total Combat Killed and Wounded = 10,683

- Total Combat and non-Combat Deaths = 25,324

- Total Combat and non-Combat Wounded = 8,445

British Battle Casualties:

- Army: 43,633 total dead/ 9,372 killed in battle/ 27,000 died of disease

- Navy: 1,243 killed in battle/ 18,500 died of disease (1776–1780)/ 42,000 deserted

- Loyalists:7,000 total dead/ 1,700 killed in battle/ 5,300 died of disease (estimated)

- Germans:7,774 total dead/ 1,800 killed in battle/ 4,888 deserted

Facts Prisoners of War (P.O.W.) in the American Revolution

American prisoners captured before 1778 were not legally ‘prisoners of war’. Not until March 25, 1782, (six months after Yorktown) did Parliament pass a law designating Americans as prisoners of war, allowing them to be detained, released or exchanged.

This provided the British with a free hand to treat their captives in any manner they saw fit.

Prisoners of War Facts

- There were thousands of American prisoners held by the British during the war.

- Of all of the prisoners held in captivity, 4 out of 5 men died.

- New York City was the main city where prisoners were held.

- By the end of 1776, there were over 5,000 prisoners held in New York City. More than half of the prisoners came from the soldiers captured at the battle of Fort Washington and Fort Lee. With a total population of New York City around 25,000, this meant that 1 out of every 5 people in the city were prisoners.

- During the war, more military men on the British prison ships than were killed in battle.

- A Prisoner Exchange Program was used between the British and American forces during the American Revolutionary War. The premise of the exchange was to be able to exchange a sailor for a sailor, a soldier for a soldier, with the prisoners being of equal rank. Later on in the war, the exchange program was stopped by the British in 1780.The reason being that with the American forces being smaller than the British forces, the British didn’t want to let the Americans get back more of their men by using the rate of attrition being that the Americans didn’t have nearly as many military personnel as the British.After the major British defeat at the battle of Yorktown in 1781, the British wanted to restart the program due to the severe shortage of soldiers and sailors in the British military. Gen. George Washington realized this, and with the war coming to an end with the Americans seeing that they were going to be victorious, decided to not start the program back.

- Prisoners on board the British prison ships could win their release if they signed an oath to serve as sailors with the British Royal Navy.

- In the latter years of the war, the number of enlistments of British sailors were becoming smaller and more difficult to fulfill. To offset the low recruiting numbers, the British government authorized a plan whereas the American prisoners would be allowed to sign an oath to serve in the Royal Navy in exchange for being released from captivity as prisoners of war.

- By the end of the war, almost 25% of the sailors serving aboard ships in the British Royal Navy were former American prisoners who signed the oath.

Latest from the Blog

Shadow Hover Effect

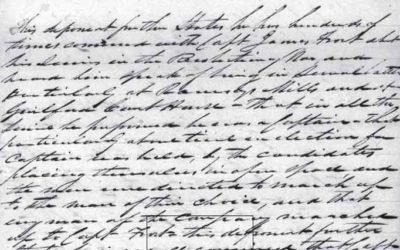

Revolutionary War Pension Files

If you have ancestors who served in the Revolutionary War, Fold3’s Revolutionary War Pension Files can be a valuable resource for finding detailed information about them and their families. With roughly 80,000 files, this collection (via the National Archives) contains applications for veterans’ pensions, widows’ pensions, and bounty land warrants, organized by state and then by veteran surname.

(more…)