The Battle of Guilford Courthouse

March 15, 1781 at Guilford County, North Carolina

Battle Summary

The Battle of Guilford Court House was fought at a site which is now in Greensboro, the county seat of Guilford County, North Carolina. A 2,100-man British force defeated Major General Nathanael Greene's 4,500 Americans. The British Army, however, lost a considerable number of men during the battle (with estimates as high as 27%). Such heavy British casualties resulted in a strategic victory for the Americans.

The battle was “the largest and most hotly contested action” in the Revolution’s southern action, and led to the surrender of Lieutenant General Charles Cornwallis at the Battle of Yorktown. Before the battle, the British had had great success in conquering much of Georgia and South Carolina with the aid of strong Loyalist factions, and thought that North Carolina might be within their grasp.

In fact, the British were in the process of heavy recruitment in North Carolina when this battle put an end to their recruiting drive. In the wake of the battle, Greene moved into South Carolina, while Cornwallis chose to march into Virginia and attempt to link up with roughly 3,500 men under British Major General Phillips and American turncoat Brigadier General Benedict Arnold. These decisions allowed Greene to unravel British control of the South, while leading Cornwallis to Yorktown and eventual surrender to General George Washington and Lieutenant General Comte de Rochambeau.

Facts about the Battle of Guilford Courthouse

- Armies - American Forces was commanded by Maj. Gen Nathaniel Greene and consisted of about 4,400 Soldiers. British Forces was commanded by Gen. Charles Cornwallis and consisted of about 1,900 Soldiers.

- Casualties - American casualties were about 79 killed, 185 wounded, 75 captured, and 1,046 missing. British casualties were 93 killed, 413 wounded, and 26 missing/captured.

- Outcome - The result of the battle was a tactical British victory. The battle was part of the Southern Theater 1775-82.

Prelude

Following the Battle of Cowpens, Cornwallis was determined to destroy Greene's army. However, the loss of his light infantry at Cowpens led him to burn his supplies so that his army would be nimble enough for pursuit. He chased Greene in the Race to the Dan, but Greene escaped across the flooded Dan River to safety in Virginia.

Cornwallis established camp at Hillsborough and attempted to forage supplies and recruit North Carolina's Tories. However, the bedraggled state of his army and Pyle's massacre deterred Loyalists.

On March 8, Brigadier General Daniel Morgan and Greene's forces met at Guilford Courthouse. Greene met with his officers and asked what their next move should be. They all decided to continue the northward retreat. That retreat was known as the "Race for the Dan." The Dan River was swollen and only safe to cross at upstream fords, along the border of North Carolina and Virginia.

Greene continued to stay ahead of Cornwallis. Cornwallis knew that his large wagon trains were slowing him down. He decided to burn all items that were not necessary for battle and left stragglers behind so that the army could move faster. Greene had detached a decoy force, commanded by Otho Williams, to lure Cornwallis in the opposite direction of the main retreating army. The decoying force succeeded in getting the British to chase them instead of Greene.

Cornwallis moved his army between the Americans and the upstream fords. Greene had collected enough boats to carry his army across the river at a point downstream from the British position. Greene knew that the British would be worn out from fast marching over 200 miles.

Cornwallis arrived just in time to see the last boatload of Americans make it across the river. Since he did not have any boats, he turned his army around in disgust and headed to Hillsboro.

In early March, Greene rested and reorganize his army. He was waiting for promised reinforcements from Virginia to arrive before moving back into North Carolina to attack the British. After learning that Cornwallis was retiring south, Greene sent a detachment across the river to shadow the British and harass them, which they did for a couple of weeks.

A few days later, 600 Virginia militiamen arrived. With his reinforcements, which brought his total to 2,100 men, Greene now had twice as many troops as the British. He led his army back across the Dan River and headed to Guilford Courthouse. Once back in North Carolina, Greene's force quickly increased in size. About 400 Virginia Continentals arrived with Col. Richard Campbell, about 1,000 North Carolina militiamen, and 1,700 Virginia militiamen.

By March 10, Greene's force had grown to 4,400 troops.

On March 12, Greene moved his army 20 miles to Guilford Courthouse, where he carefully chose his ground for a fight with the British.

On March 14, while encamped in the forks of the Deep River, Cornwallis was informed that General Richard Butler was marching to attack his army. With Butler was a body of North Carolina militia, plus reinforcements from Virginia, consisting of 3,000 Virginia militia, a Virginia State regiment, a Corps of Virginian 18-month men and recruits for the Maryland Line. They had joined the command of Greene, creating a force of some nine to ten thousand men in total.

On March 15, during the night, further reports confirmed the American force was at Guilford Court House, some 12 miles away.

Cornwallis decided to give battle, though he had only 1,900 men at his disposal. He detached his baggage train, 100 infantry and 20 Cavalry under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Hamilton to Bell's Mills further down the Deep River, then set off with his main force, before breakfast was able to be eaten, arriving at Guilford at midday. Meanwhile, Greene, having received the reinforcements, decided to recross the Dan and challenge Cornwallis.

The two armies met at Guilford Court House, North Carolina (within the present Greensboro, North Carolina).

Battle Begins

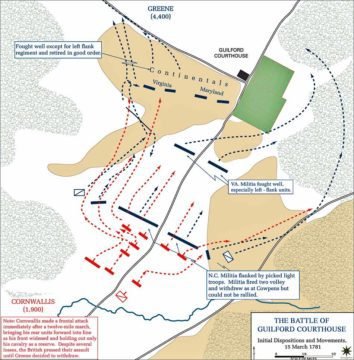

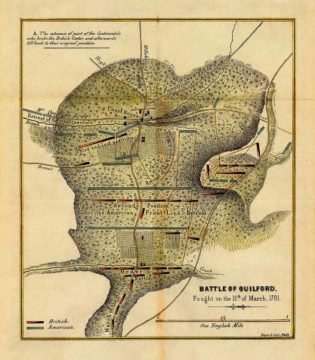

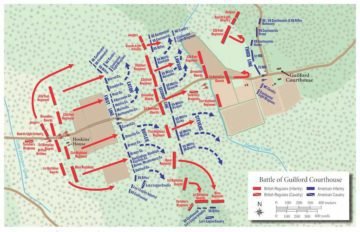

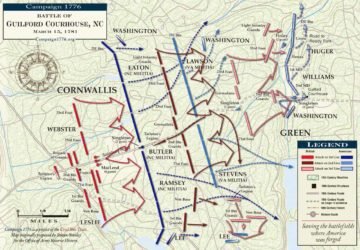

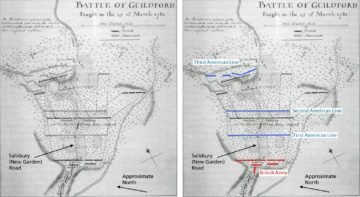

On March 15, Greene had divided his force into three seperate lines of infantry supported by cavalry and artillery. Each line of battle was perpendicular to the New Garden Road, which ran through Greene's lines west to east before intersecting with the road from Reedy Fork behind the Americans. Guilford Courthouse sat within a T-intersection formed by the junction of these roads.

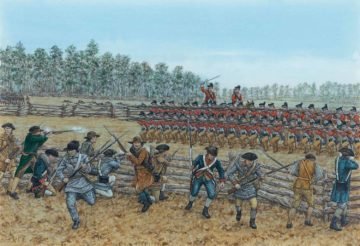

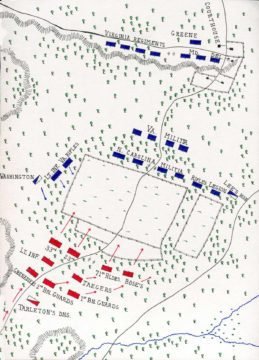

The first line, behind a rail fence with the woods to their back, was made up of about 1,000 North Carolina militia, commanded by Brigadier General John Butler and Colonel Thomas Eaton. In the center of the line was two small artillery pieces on the road. They could fire on the British while they crossed the open fields. The first line's left flank was supported by Lee's Legion and Campbell's Continentals. The right flank was supported by Lieutenant Colonel William Washington's calvary and Colonel Charles Lynch's Riflemen.

The second line, about 350 yards behind and further east in the heavy woods, was made up of 1,200 Virginia militia with a mixture of previously discharged Continental veterans. Here, they would provide cover for the first line. The third line, another 500 yards further to the rear on a slight rise near the courthouse, was the main line of battle consisting of 1,400 Continentals from Virginia, Delaware, and Maryland on the west side of the road.

Cornwallis approached the American positions from the west along New Garden Road about midday. In his ranks were slightly less than 2,000 men. About 4 miles west of Guilford Courthouse, some of Greene's advance guard of cavalry, commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Henry Lee, and dismounted infantry skirmished by using some harassing fire against the approaching British. A running battle eastward broke out.

At 1:00 P.M., the British crossed Little Horsepen Creek (1/2 mile beyond the creek was the American positions) and deployed for their attack. Cornwallis brought his artillery to the front to counter the American artillery fire. He then divided his army into 2 wings on either side of New Garden Road. The left wing was commanded by Colonel James Webster and the right wing was commanded by Major General Alexander Leslie. Tarleton's Legion was held in the rear as a reserve force.

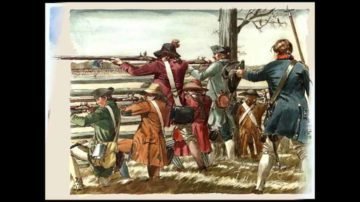

The British advanced and when they approached within killing range, the Americans fired on them. The British continued their advanced, fired a volley, and then made a bayonet charge. The Americans leveled their muskets on the fence and fired a second volley. This volley was noted as one of the most effective single volley of the war. The British troops were surprised that the militia did not run away from the bayonet charge. This is what the American militia usually did before.

The British steadied their line and continued their advance. The first line of militia melted away, along with the cavalry and infantry on the flanks. This was able to siphon the British strength from the main battle.

The British moved toward the American second line. With the Americans deployed on wooded and hilly terrain, groups of them were able to surprise parts of the British line. Fighting an uphill battle confused the British, which began to lose their cohesion. The fight at the second line was a much harder and deadlier than the first line. The British were able to overlap the American right, bend it back, and soon made it collapse.

Without much time to reorganize, Cornwallis ordered his troops forward where they soon ran into the last American line, which was its strongest. Webster launched a quick uphill attack on the American left. It was quickly repulsed and Webster was mortally wounded. On the British right wing, a bayonet charge was ordered to attack the American left.

The British temporarily overran part of the American line and captured two artillery pieces. Greene saw this and ordered Washington's cavalry and infantry to seal the breach in the line. They engaged in a hand-to-hand fight with the British, recaptured the artillery, and sealed the breach.

Cornwallis made a controversial call, deciding to bring up his artillery and fire over his own troops into the American line. This desperate move killed as many British troops as it did Americans, but it did halt the American counterattack. Tarleton was ordered to take his cavalry and engage the Americans.

Thinking that his men were about to be driven from the field and accomplishing all that was possible, Greene decided to withdraw his force from the battlefield in an orderly retreat northwest on the Reedy Road. This allowed Cornwallis to claim a victory.

Greene's decision to retreat proved to be a cautious but wise decision. Tarleton's cavalry, along with several Hessian units, swept what was left of the Amnerican force from the field. Cornwallis claimed a victory, but his forces suffered great losses.

In London, when the battle reports came in, Charles J. Fox, a member of Parliament, remarked that "Another such victory would ruin the British army."

Aftermath

The battle had lasted only 90 minutes, and although the British technically defeated the American force, they lost over a quarter of their own men.

The British, by taking ground with their accustomed tenacity when engaged with superior numbers, were tactically victors. Seeing this as a classic Pyrrhic victory, British Whig Party leader and war critic Charles James Fox echoed Plutarch's famous words by saying, "Another such victory would ruin the British Army!".

In a letter to Lord George Germain, delivered by his aide-de-camp, Captain Broderick, Cornwallis commented:"From our observation, and the best accounts we could procure, we did not doubt but the strength of the enemy exceeded 7,000 men [Greene's accounts put this closer to 4,400].... I cannot ascertain the loss of the enemy, but it must have been considerable; between 200 and 300 dead were left on the field of battle.... many of their wounded escaped.... Our forage parties have reported to me that houses in a circle six to eight miles around us are full of others.... We took few prisoners".

He further went on to comment on the British force:"The conduct and actions of the officers and soldiers that composed this little army will do more justice to their merit than I can by words. Their persevering intrepidity in action, their invincible patience in the hardships and fatigues of a march of above 600 miles, in which they have forded several large rivers and numberless creeks, many of which would be reckoned large rivers in any other country in the world, without tents or covering against the climate, and often without provisions, will sufficiently manifest their ardent zeal for the honour and interests of their Sovereign and their country."

After the battle, the British were spread across a large expanse of woodland without food and shelter, and during the night torrential rains started. Had the British followed the retreating Americans they may have come across their baggage and supply wagons, which had been camped up to the west of the Salisbury road in some old fields prior to the battle.

Greene, cautiously avoiding another Camden, retreated with his forces intact. With his small army, less than 2000 strong, Cornwallis declined to follow Greene into the back country, and retiring to Hillsborough, he raised the royal standard, offered protection to the inhabitants, and for the moment appeared to be master of Georgia and the two Carolinas. In a few weeks, however, he abandoned the heart of the state and marched to the coast at Wilmington, North Carolina, to recruit and refit his command.

At Wilmington, the British general faced a serious problem, the solution of which, upon his own responsibility, unexpectedly led to the close of the war within seven months. Instead of remaining in Carolina, he determined to march into Virginia, justifying the move on the ground that until Virginia was reduced he could not firmly hold the more southern states he had just overrun. This decision was subsequently sharply criticized by General Henry Clinton as unmilitary, and as having been made contrary to his instructions.

To Cornwallis, he wrote in May: "Had you intimated the probability of your intention, I should certainly have endeavoured to stop you, as I did then as well as now consider such a move likely to be dangerous to our interests in the Southern Colonies." For three months he raided every farm or plantation he came across, from whom he took hundreds of horses for his Dragoons. He also converted another 700 infantry to mounted duties. During these raids he freed thousands of slaves, of which 12,000 joined his own force.

The danger lay in the suddenly changed situation in that direction; as Greene, instead of following Cornwallis to the coast, boldly pushed down towards Camden and Charleston, South Carolina, with a view to drawing his antagonist after him to the points where he was the year before, as well as to driving back Lord Rawdon, whom Cornwallis had left in that field.

In his main object—the recovery of the southern states—Greene succeeded by the close of the year, but not without hard fighting and repeated reverses. "We fight, get beaten, and fight again," were his words.

On March 19, Major Charles Magill reported to Governor Jefferson that Cornwallis had taken custody of 75 wounded Americans.

“Return of ordnance, ammunition, and arms, taken at the battle of Guildford, March 15, 1781. Brass Ordnance: Mounted on travelling carriages, with limbers and boxes complete, 4 six-pounders. Shot, round, fixed with powder, 160 six-pounders. Case, fixed with ditto, 50 six-pounders; 2 ammunition waggons, 1300 stands of arms distributed among the militia, and destroyed in the field.”

Cornwallis to Lord Germain, dated from Guilford, March 17, 1781: “The neighborhood of the Fords of the Dan in their rear, and the extreme difficulty of subsisting my troops in that exhausted country putting it out of my power to force them, my resolution was to give our friends time to join us, by covering their country; ...at the same time I was determined to fight the rebel army. With these views, I moved to the Quaker Meetting (house), in the forks of Deep River, on the 13th; and on the 14th I received the information which occasioned the movement which brought about the action at Guildford..."

Kirkwood: "15th. This day commenced the Action at Guilford Court House between Genls. Green and Cornwallis, in which many were Killed and wounded on both sides, Genl. Green Drew off his Army, with the loss of his artillery. Marched this day ......16" [miles].

Pension statement of James Roper, of Caswell County, N.C. “In his 3rd campaign he served under Capt. Edward Dickerson and marched from the Court House to meet the brigade of Gen. Butler and marched to Ravin Town to Gen. Green's army across the Haw River along with Gen. Eaton's brigade marched to Guilford Courthouse to engage the British Army under Lord Cornwallis. The first line up to battle consisted of the North Carolina Militia under Gen. Butler & Eaton. About the time Gen. Green had his army arrayed for battle Cornwallis came up with his troops, and a desparate battle ensued. This affiant states as well as he can now recollect that it was about one or two oclock of the day P.M. when the battle began between Gen. Green & Cornwallis. The battle lasted for some time with various success on both sides and at last Gen. Green had to retreat & leave the battle ground.”

Davie (who was present at the battle): "[Gordon] speaks true to be sure of the No Carolian militia as they deserved, but it is justice to observe they were never so wretchedly officered as they were that day – but he attributes the glory acquired by Stevens brigade to the whole Virginia Militia, when the truth is Lawson's brigade fought as illy as the No Carolinians The only difference was they did not run entirely home...the fact is the whole battle was fought by Stevens brigade and the first Maryland regiment.:." Referring, in a different writing, to the clash between the Guards and the 1st Maryland Regt., Davie says: “[Capt. John] Smith and his men were in a throng, killing the Guards and Grenadiers like so many Furies. Colonel Stewart [James Stuart], seeing the mischief Smith was doing, made a lunge at him with his small sword…It would have run through his body but for the haste of the Colonel, and happening to set his foot on the arm of the man Smith had just cut down, his unsteady step, his violent lunge, and missing his aim brought him down to one knee on the dead man. The Guards came rushing up very strong. Smith had no alternative but to wheel around and give Stewart a back-handed blow over or across the head, on which he fell.”

Seymour: "Colonel Washington, with his cavalry, in this action deserved the highest praise, who meeting with the Third Regiment of Foot Guards, and charged them so furiously that they either killed or wounded almost every man in the regiment, charging through them and breaking their ranks three or four times. This action began about nine o' clock in the morning and continued about the space of an hour and a half, in which the enemy lost in killed and wounded fifteen hundred men, our loss not exceeding one hundred and fifty in killed and wounded, of which twenty-seven belonged to Col. Washington's Light Infantry, of which Captain Kirkwood had the command."

Tarleton: “The thickness of the woods where these conflicts happened prevented the cavalry making a charge upon the Americans on their retreat to the continentals, and impeded the British infantry moving forwards in a well-connected line. Some corps meeting with less opposition and embarrassment than others, arrived sooner in presence of the continentals, who received them with resolution and firmness.At this period the event of the action was doubtful, and victory alternately presided over each army. On the left of the British Colonel Webster carried on the yagers, the light company of the guards, and the 33d regiment, after two severe struggles, to the right of the continentals, whose superiority of numbers and weight of fire obliged him to recross a ravine, and take ground upon the opposite bank.This manoeuvre was planned with great judgement, and, being executed with coolness and precision, gave Webster an excellent position till he could hear of the progress of the King's troops upon his right. In the center the 2d battalion of the guards, commanded by Lieutenant-colonel Stewart, supported by the grenadiers, made a spirited and successful attack on the enemy's six pounders, which they took from the Delaware regiment; but the Maryland brigade, followed by Washington's cavalry, moving upon them before they could receive assistance, retook the cannon, and repulsed the guards with great slaughter. The ground being open, Colonel Washington's dragoons killed Colonel Stewart and several of his men, and pursued the remainder into the wood.

General O'Hara, though wounded, rallied the remainder of the 2d battalion of the guards to the 23d and 71st regiments, who had inclined from the divisions on the right and left, and were now approaching the open ground. The grenadiers, after all their officers were wounded, attached themselves to the artillery and the cavalry, who were advancing upon the main road. At this crisis, the judicious use of the three pounders, the firm countenance of the British infantry, and the appearance of the cavalry, obliged the enemy to retreat, leaving their cannon and ammunition waggons behind them. Colonel Webster soon after connected his corps with the main body, and the action on the left and in the center was finished.

Earl Cornwallis did not think it advisable for the British cavalry to charge the enemy, who were retreating in good order, but directed Lieutenant-colonel Tarleton to proceed with a squadron of dragoons to the assistance of Major-general Leslie on the right, where, by the constant fire which was yet maintained, the affair seemed not to be determined. The right wing, from the thickness of the woods and a jealousy for its flank, had imperceptibly inclined to the right, by which movement it had a kind of separate action after the front line of the Americans gave way, and was now engaged with several bodies of militia and riflemen above a mile distant from the center of the British army. The 1st battalion of the guards, commanded by Lieutenant-colonel Norton, and the regiment of Bose, under Major De Buy [de Puis], had their share of the difficulties of the day, and, owing to the nature of the light troops opposed to them, could never make any decisive impression:

As they advanced, the Americans gave ground in front, and inclined to their flanks: This sort of conflict had continued some time, when the British cavalry, on their way to join them, found officers and men of both corps wounded, and in possession of the enemy: The prisoners were quickly rescued from the hands of their captors, and the dragoons reached General Leslie without delay. As soon as the cavalry arrived, the guards and the Hessians were directed to fire a volley upon the largest party of the militia, and, under the cover of the smoke, Lieutenant-colonel Tarleton doubled round the right flank of the guards, and charged the Americans with considerable effect. The enemy gave way on all sides, and were routed with confusion and loss. Thus ended a general, and, in the main, a well-contested action, which had lasted upwards of two hours. General Leslie soon afterwards joined Earl Cornwallis, who had advanced a short distance on the Reedy-fork road, with the 23d and 71st regiments, to support the other squadron of the British legion, who followed the rear of the continentals.”

Sgt. Roger Lamb of the 23rd Regt.: “[After the battle] Every assistance was furnished to them [the wounded of both sides], that in the then circumstances of the army could be afforded; but, unfortunately the army was destitute of tents, nor was there a sufficient number of houses near the field of battle to receive the wounded. The British army had marched several miles on the morning of the day on which they came to action. They had no provisions of any kind whatever on that day, nor until between three and four in the afternoon of the succeeding day, and then but a scanty allowance, not exceeding one quarter of a pond of flower, and the same quantity of very lean beef. The night of the day on which the action happened was remarkable for its darkness, accompanied by rain which fell in torrents. Near fifty of the wounded, it is said, sinking under their aggravated miseries, expired before morning. The cries of the wounded, and dying who remained on the field of action during the night, exceeded all description. Such a complicated scene of horror and distress, it is hoped, for the sake of humanity, rarely occurs, even in a military life.”