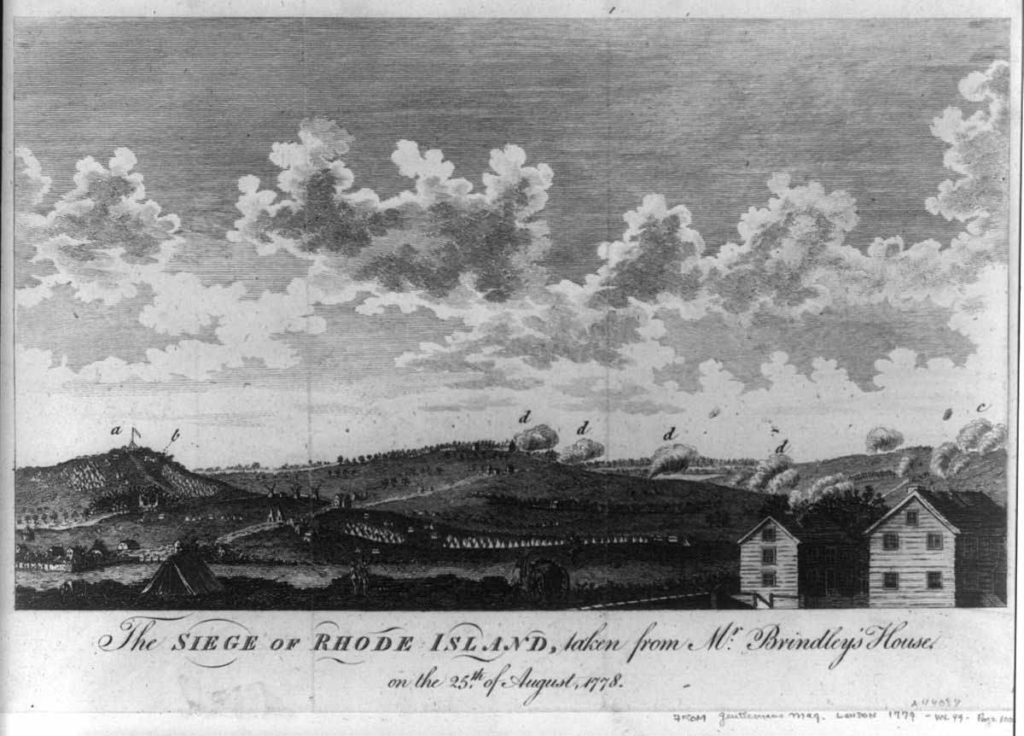

The Battle of Rhode Island

August 29, 1778 in Newport, Rhode IslandThe Battle of Rhode Island was also known as the Battle of Quaker Hill and the Battle of Newport. Continental Army and militia forces were withdrawing to the northern part of Aquidneck Island after abandoning their siege of Newport, Rhode Island when the British forces in Newport sortied, supported by recently arrived Royal Navy ships, and attacked the retreating Americans.

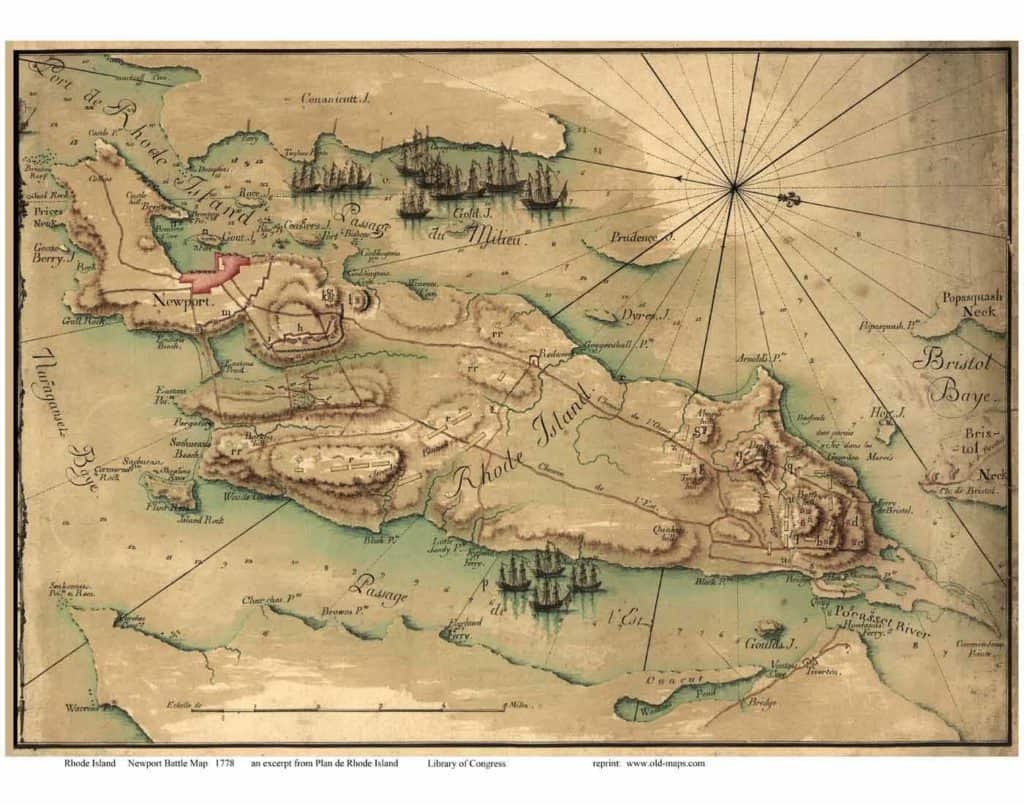

Map of the Battle of Rhode Island

The battle ended inconclusively, but afterwards Continental forces withdrew to the mainland, leaving Aquidneck Island in British hands.

Facts about the Battle of Rhode Island

- American Forces was commanded by Col. John Sullivan and consisted of about 10,100 Soldiers.

- American casualties were estimated to be 30 killed, 173 wounded, and 44 missing.

- British Forces was commanded by Gen Sir Robert Pigot and consisted of about 7,139 Soldiers.

- British casualties were estimated to be 38 killed, 210 wounded, and 12 missing.

- The battle was the first attempt at cooperation between French and American forces following France’s entry into the war as an American ally.

- Operations against Newport were planned in conjunction with a French fleet and troops, but they were frustrated in part by difficult relations between the commanders, as well as by a storm that damaged both French and British fleets shortly before joint operations were to begin.

- The battle was also notable for the participation of the 1st Rhode Island Regiment under the command of Colonel Christopher Greene, which consisted of Africans, American Indians, and white colonists.

- The result of the battle was a British victory. The battle was part of the Northern Theater 1778-82.

Prelude

Many thousands of men were gathered at Fort Barton in the summer and fall of 1777 for an October invasion of Aquidneck.

However, because of the allowance of insufficient time for the amassing of materiel, the inexperience of the officer-in-charge, and the accompanying bad weather at the designated times of invasion, two half-hearted attempts to establish beachheads across Howland’s Ferry were thwarted.

In the spring, General George Washington selected Major General John Sullivan to assume command of Fort Barton and to direct staging operations for a new invasion attempt of Aquidneck. Major General Marquis de Lafayette was to coordinate the participation of a French fleet and landing force, and a Grande Plan of a strike by land and sea was formulated.

On August 9, the Battle of Rhode Island began with the crossing at Howland’s Ferry of 11,000 Continental line troops and militia. The French navy blocked Narragansett Bay, forcing the British to scuttle their small naval force.

The American army, under Sullivan, landed at Rhode Island and forced the smaller British/German force to withdraw behind fortifications built around the town of Newport.

Within a few days, a large British naval force arrived to challenge the French fleet. The French fleet sailed out of the bay to do battle in the open ocean. As the two fleets maneuvered, preparing for battle, a hurricane came upon them and scattered the fleets from August 13-14, causing severe damage to both sides.

For the land forces, the high winds and rain also did great damage to both sides, but the British defenders faired better because they were behind prepared positions and in a town. For the next week, elements of the scattered French fleet returned to the bay.

On August 22, the French ships sailed to Boston for repairs. Lafayette’s disappointment at a reduced role of command, the French Adm. d’Estaing’s failure to contribute landing troops, and the severe damage sustained by the French fleet brought the full force of the defending British, Hessian and Loyalist troops to bear on the hardy invaders from Tiverton’s shores.

Without the sea attack to draw the attention of many of the defenders away from the land attack, the British line held.

The American army, which was much larger than the British, was composed largely of short-term militia soldiers who had joined up just for this campaign. When the French fleet sailed away, they became very discouraged, knowing that they could not take the town and hold it without strong naval support.

By the end of the month, the dishearten army began to withdrawal. The French departure prompted a mass exodus of the American militia, significantly shrinking the American force, many of whom had only enlisted for a 20-day stint, anyway.

On August 24, Sullivan was alerted by Washington that General Henry Clinton was in New York, assembling a relief force. That evening, his council made the decision to withdraw to positions on the northern part of the island.

Sullivan continued to seek French assistance, dispatching Lafayette to Boston to negotiate further with d’Estaing, but this proved fruitless in the end. D’Estaing and Lafayette met fierce criticism in Boston, Lafayette remarking that

“I am more upon a warlike footing in the American lines than when I came near the British lines at Newport.”

In the meantime, the British in New York had not been idle. General William Howe was reinforced by the arrival of ships from Byron’s storm-tossed squadron, and he sailed out to catch d’Estaing before he reached Boston.

On August 26, Clinton organized a force of 4,000 men under Major General Charles Grey and sailed with it to Newport.

Battle Begins

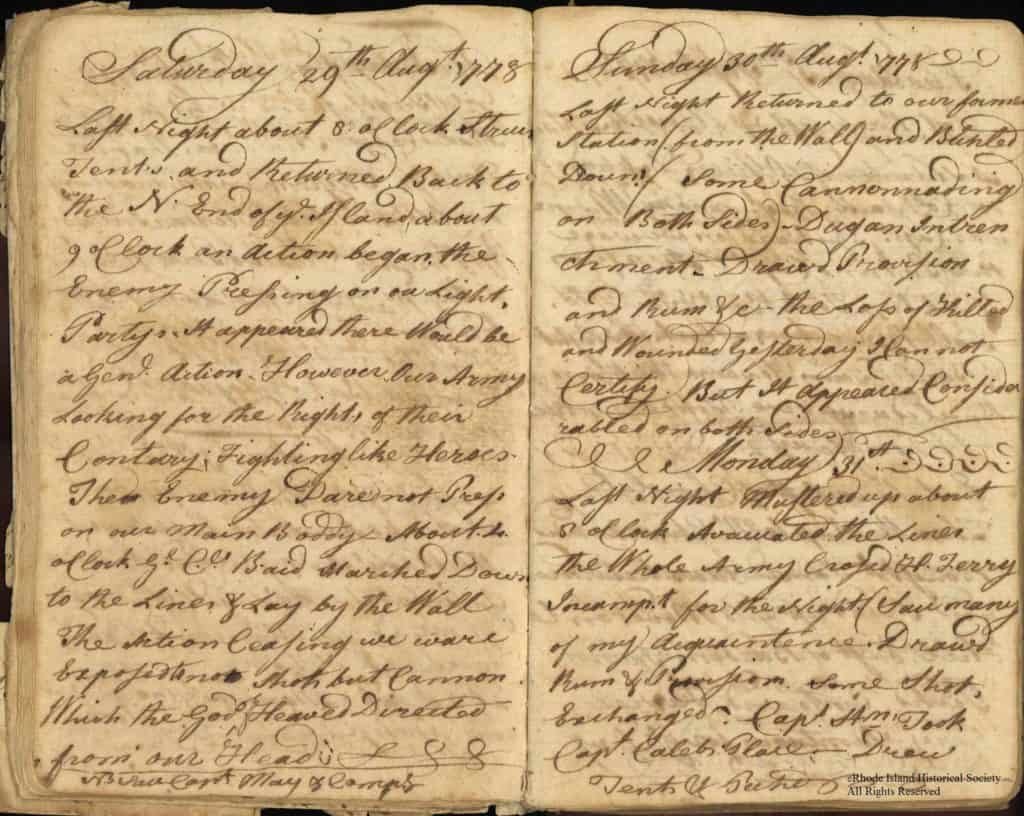

On the morning of August 28, the American war council decided to withdraw the last troops from their siege camps. They had engaged the British with occasional rounds of cannon fire for a few days, as some of their equipment was being withdrawn.

Deserters had made General Pigot aware of the American plans to withdraw on August 26, so he was prepared to respond when they withdrew that night.

On August 29, the British perceived that the Americans were attempting to leave the island, and sallied out of their lines to attack, hoping to disrupt the retreat.

The Americans were moving to the north end of the long, narrow island, and crossing the narrow water to the mainland. The Americans made a stand on Butt’s Hill, 12 miles from Newport, which they had fortified.

The British tried to turn their right wing in the morning, when Greene, commanding it, changed front, assailed the pursuers vigorously, and drove them to their strong defense on Quaker Hill.

A general engagement ensued, when the British line was broken and driven back in confusion to Turkey Hill. The day was very sultry, and many perished by the heat. The action ended at near 3:00 P.M., but a sluggish cannonade was kept up until sunset.

The 1st Rhode Island, the first black regiment in America’s history, took part in the action.

Battle of Rhode Island desperate valor

Located on the right (west) side of the American line, they defended their part of the hill against fierce attacks by German troops. Numbering 400 men, the 1st Rhode Island acquitted itself well, repulsing three separate and distinct charges from 1,500 Hessians under Count Donop.

They beat them back with such tremendous loss that Donop at once applied for an exchange, fearing that his men would kill him if he went into battle with them again, for having exposed them to such slaughter.

After a siege of 12 days by the Americans dug in on Honeyman’s Hill in Middletown, a weary and disappointed Sullivan realized the land attack alone could not penetrate the English line. With extreme regret, Sullivan was obliged to order withdrawal.

On August 30, near midnight, the last of the Continentals was removed from Aquidneck. The regular troops were sent to rejoin Washington, the militia returned home, and only a small force was left to man the guns of Fort Barton. The Battle of Rhode Island was over.

Aftermath

On August 30, during the night, Continental forces withdrew to Bristol and Tiverton, leaving Rhode Island (Aquidneck Island) under British control. However, their withdrawal was orderly and unhurried.

According to an account in the New Hampshire Gazette, it was accomplished

“in perfect order and safety, not leaving behind the smallest article of provision, camp equipage, or military stores.”

The inflammatory writings of Sullivan reached Boston before the French fleet arrived, and Admiral d’Estaing’s initial reaction was reported to be a dignified silence.

Politicians worked to smooth over the incident under pressure from Washington and the Continental Congress, and d’Estaing was in good spirits when Lafayette arrived in Boston.

He even offered to march troops overland to support the Americans:

“I offered to become a colonel of infantry, under the command of one who three years ago was a lawyer, and who certainly must have been an uncomfortable man for his clients.”

On September 1, the relief force of Clinton and Grey arrived at Newport. Given that the threat was over, Clinton ordered Grey to raid several communities on the Massachusetts coast. Admiral Richard Howe was unsuccessful in his bid to catch up with d’Estaing, who held a strong position at the Nantasket Roads when Howe arrived there on August 30.

Byron succeeded Howe as head of the New York station in September, but he also was unsuccessful in blockading d’Estaing. His fleet was scattered by a storm when it arrived off Boston, after which d’Estaing slipped away, bound for the West Indies.

Pigot was harshly criticized by Clinton for failing to await the relief force, which might have successfully entrapped the Americans on the island. He left Newport for England not long after. The British abandoned Newport in October 1779, leaving behind an economy ruined by war.