The Battle of Paoli (Massacre)

September 21, 1777 at Malvern, Pennsylvania

Battle Summary

The Battle of Paoli was also known as the Battle of Paoli Tavern or the Paoli Massacre. Following the American retreats at the Battle of Brandywine and the Battle of the Clouds, General George Washington left a force under Brigadier General Anthony Wayne behind to monitor and harass the British as they prepared to move on the revolutionary capital of Philadelphia.

On the evening of September 20, British forces under Major General Charles Grey led a surprise attack on Wayne's encampment near the Paoli Tavern. Although there were relatively few American casualties, claims were made that the British took no prisoners and granted no quarter, and the engagement became known as the "Paoli Massacre."

Facts about the Battle of Paoli (Massacre)

- Armies - American Forces was commanded by Gen. Anthony Wayne and consisted of about 1,500 Soldiers. British Forces was commanded by Gen. Charles Gray and consisted of about 5,000 Soldiers.

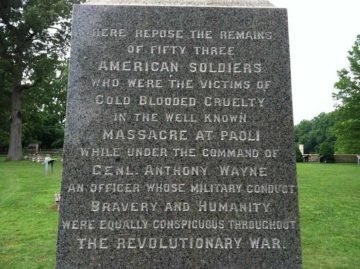

- Casualties - American casualties were estimated to be 53 killed, 113 wounded, and 71 missing/captured. British casualties were about 4 killed and 7 wounded.

- Outcome - The result of the battle was a British victory. The battle was part of the Philadelphia Campaign 1777-78.

Prelude

After the American defeat at Brandywine, Washington was intent on accomplishing two tasks. He wanted to protect Philadelphia from British forces under the command of Lieutenant General William Howe, and he needed to replenish the rapidly dwindling supplies and munitions stored in Reading, Pennsylvania. Washington withdrew across the Schuylkill River, marched through Philadelphia, and headed northwest.

Since the Schuylkill River was fordable only far upstream starting at Matson's Ford (present-day Conshohocken), Washington could protect both the capital and the vital supply areas to the west from behind the river barrier. Washington reconsidered, and recrossed the river to face the British, who had moved little since Brandywine, due to a shortage of wagons to carry their wounded and their baggage.

On September 16, after the Battle of the Clouds was aborted by bad weather, Washington again withdrew across the Schuylkill, leaving Wayne's Pennsylvania Division at Chester, Pennsylvania. When the British columns passed by, Wayne followed to harass the British and attempt to capture all or part of their baggage train.

Wayne assumed that his presence was undetected and camped close to the British lines in Paoli, Pennsylvania. His division consisted of the 1st, 2nd, 4th, 5th, 7th, 8th, 10th and 11th Pennsylvania Regiments, Hartley's Regiment, an attached artillery company and a small force of dragoons. All told, it was about 1,500 strong. Camped about one mile away was William Smallwood's Maryland militia, about 2,100 relatively inexperienced troops.

The British heard rumors that Wayne was in the area. Howe sent out spies who reported his location near the Paoli Tavern on September 19. Since his position was just four miles from the British camp at Tredyffrin, Howe immediately planned an attack on Wayne's relatively exposed camp.

There was a strong loyalist presence in Pennsylvania and the British had good intelligence during the campaign. In addition, 18th Century warfare was in many respects a casual business and it seems likely that soldiers from both sides frequented the taverns, particularly the Paoli which lay part way between the camps. Howe was fully aware of Wayne’s presence and had precise knowledge of his strength.

On September 20, during the night, Howe dispatched Grey to deal with Wayne’s division. Grey left with his force at 10:00 P.M. and marched down the Moores Hall Road to the Admiral Warren cross-roads. As the leading British light infantry approached the junction, shots were fired by an American picket. It is said that these shots alerted the Pennsylvanian camp which lay behind woods to the South of the junction.

Battle Begins

At 10:00 PM, on September 20, Grey marched from the British camp, and launched a surprise attack on Wayne's camp, near the General Paoli Tavern. Grey's troops consisted of the 2nd Light Infantry, a composite battalion formed from the light companies of 13 regiments, plus the 42nd and 44th Foot.

At Grey’s direction, the flints had been removed from his men’s muskets to ensure that no shots gave prior warning to the Americans. The attack was to be at the point of the bayonet. He thereby acquired the nickname of “No Flints” Grey.

The British, led by a local blacksmith forced to act as guide, approached the camp from a wood and were able to achieve complete surprise. They stormed the camp in three waves—the 2nd Light Infantry in the lead, the 44th Foot in the second wave, and the 42nd Highlanders in the third wave. A small group of 16th Light Dragoons accompanied the Light Infantry.

Completely unprepared, Wayne's troops fled from the camp and were pursued. Near the White Horse Tavern, the British encountered Smallwood's force and routed it as well. The British had routed an entire American division.

In the face of the British charge, the Pennsylvania troops were dispersed and driven out of the camp to the West, many through a gap in a fence along the edge of the encampment. Groups of British soldiers mixed with the Americans and confused fighting continued as far as the White Horse Tavern.

Smallwood’s force approached from the West as the attack was coming to an end and came under attack as it passed the White Horse Tavern. The inexperienced and badly organised Maryland Militia dissolved in confusion.

The Battle of Paoli was a severe humiliation for the Pennsylvania Continental troops but probably little more. The fight is referred to as the "Paoli Massacre". It is difficult to see how that label can be justified in the light of the small number of American fatalities. Claims are made that the British took no prisoners. This allegation appears frequently in the Revolutionary War and is made against both sides.

Aftermath

The accusation was made against Wayne that he allowed his camp to be surprised. At his demand, he was subject to a court martial which exonerated him of this allegation. Whether he was taken unawares or not the attack was well executed and highly successful, enabling Howe to take Philadelphia within a few days with little further resistance from the main American, army under Washington.

Following the battle, the Americans vowed to take vengeance on the British Light Infantry. To show their defiance, the Light Companies of the 46th and 49th Foot, who were both part of the 2nd Light Infantry, dyed their hat feathers red so the Americans would be able to identify them. The Royal Berkshire Regiment, which carries on the traditions of the 49th Foot, still wears a red backing behind their cap badges to commemorate this.

An official inquiry found that Wayne had made a tactical error. He was enraged and demanded a full court-martial.

On November 1, a board of 13 officers declared that Wayne had acted with honor.

The incident gained some notoriety with rumors that the British had stabbed or burned Americans who tried to surrender, making martyrs out of the casualties and the battle was dubbed, "the Paoli Massacre". Military historian Mark M. Boatner III has this to say on the matter: “American propagandists succeeded in whipping up anti-British sentiment with false accusations that Grey’s men had refused quarter and massacred defenseless patriots who tried to surrender…The “no quarter” charge is refuted by the fact that the British took 71 prisoners. The “mangled dead” is explained by the fact that the bayonet is a messy weapon”.