The Battle of Cooch's Bridge

September 3, 1777 at Iron Hill, Delaware

Battle Summary

The Battle of Cooch's Bridge was also known as the Battle of Iron Hill. It was between the Continental Army and American militia and primarily German soldiers serving alongside the British Army. It was the only significant military action during the war on the soil of Delaware (though there were also naval engagements off the state's coast).

It took place about a week before the major Battle of Brandywine. Reportedly, the battle that saw the first flying of the U.S. flag.

On August 25, after landing in Maryland as part of a campaign to capture Philadelphia, the seat of the Continental Congress, British and German forces under the overall command of General William Howe began to move north. Their advance was monitored by a light infantry corps of Continental Army and militia forces that had based itself at Cooch's Bridge, near Newark, Delaware.

On September 3, German troops leading the British advance were met by musket fire from the U.S. light infantry in the woods on either side of the road leading toward Cooch's Bridge. Calling up reinforcements, they flushed the Americans out and drove them across the bridge.

Facts about the Battle of Cooch's Bridge

- Armies - American Forces was commanded by Gen. William Maxwell and consisted of about 1,000 Soldiers. British Forces was commanded by Lt Col. Ludwig Vol Wurm and consisted of about 4,000 Soldiers.

- Casualties - American casualties were estimated to be 30 killed/wounded and 140 missing/captured. British casualties was approximately 30 killed or wounded and 35 captured.

- Outcome - The result of the battle was a British victory. The battle was part of the Philadelphia Campaign 1777-78.

Prelude

On August 25, Howe's army disembarked below a small town called Head of Elk (now known as Elkton, and located at the head of navigation of the Elk River) in Maryland, about 50 miles south of Philadelphia. Due to the relatively poor quality of the landing area, his troops moved immediately to the north, reaching Head of Elk itself on August 28.

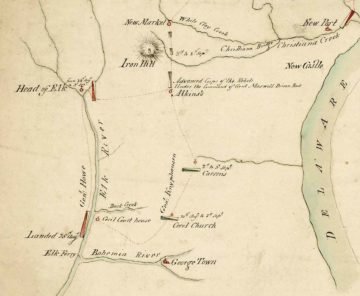

Advance troops consisting of British light infantry and German Jäger moved east across Elk Creek and occupied Gray's Hill, about one mile west of Iron Hill, near Cooch's Bridge, which was a few miles south of Newark. The bridge was named for Thomas Cooch, a local landowner whose house was near the bridge.

General George Washington would normally have assigned the duties of advance guard to Colonel Daniel Morgan and his riflemen, but he had detached these to assist Major General Horatio Gates in the defense of the Hudson River Valley against the advance of Lieutenant General John Burgoyne. Since they were unavailable, he organized a light infantry corps consisting of 700 picked men from Continental Army regiments and about 1,000 Pennsylvania and Delaware militia, and placed them under the command of Brigadier General William Maxwell. These troops occupied Iron Hill and Cooch's Bridge.

Major General Nathanael Greene advocated moving the entire Continental Army to Cooch's Bridge, believing the Christina River to be a more defensible point, but Washington declined, instead ordering Maxwell to monitor British movements and slow its advance while the rest of the army fortified the Red Clay Creek and Wilmington. Maxwell's men were encamped on either side of the road leading south from Cooch's Bridge toward Aiken's Tavern (present-day Glasgow, Delaware) in a series of small camps designed to facilitate ambushes.

On August 28, Washington, atop Iron Hill, and Howe, on Gray's Hill, observed each other as they took stock of the enemy's position; one of the Hessian generals wrote, "These gentlemen observed us with their glasses as carefully as we observed them. Those of our officers who know Washington well, maintained that the man in the plain coat was Washington."

On September 2, Howe's right wing, under the command of the Major General Wilhelm von Knyphausen, left Cecil County Court House and headed north, hampered by rain and bad roads.

On September 3, early in the morning, Howe's left wing, headed by troops under the command of Major General Charles Cornwallis, left Head of Elk, expecting to join with Knyphausen's division at Aiken's Tavern, about 5 miles east. Cornwallis reached the tavern first, and Howe, traveling with Cornwallis, decided to press on to the north without waiting for Knyphausen.

Battle Begins

A small company of Hessian dragoons led by Captain Johann Ewald headed up the road from the tavern toward Cooch's Bridge as Cornwallis's advance guard. These were struck by a volley of fire from an American ambush and many of them fell, either killed or wounded.

Ewald remained unwounded, and quickly alerted the Hessian and Ansbach Jäger, who rushed forward to meet the Americans. This began a running skirmish that Major John André described as follows: "Here the rebels began to attack us about 9 o'clock with a continued irregular fire for nearly two miles."

Howe rode to the front lines, and seeing Iron Hill crawling with enemy soldiers, ordered his troops to clear it. At this time, much of Maxwell's force was defending Iron Hill, while the rest were protecting Cooch's Bridge. The Jäger, numbering over 400 men led by Lieutenant Colonel Ludwig von Wurmb, formed a line and, with the support of some artillery, advanced on the Americans. Von Wurmb sent one detachment to Maxwell's left, hoping to flank his position, and supported the move with a bayonet charge against the American center.

The battle lasted for much of the day; at Cooch's Bridge, Maxwell's men made a stand until they "had shot themselves out of ammunition" and "the fight was carried on with the sword" and bayonet.

After seven hours of fighting, the Americans were forced to retreat from Iron Hill across Cooch's Bridge, taking up a position on the far side. Howe ordered the 1st and 2nd British Light Infantry Battalion to assist the Jäger in taking the bridge. While the 1st Battalion, under Robert Abercromby, became mired in swampy terrain attempting to ford the Christina River, the 2nd Battalion reached the right of the Jäger and the bridge was taken. Maxwell's army then retreated back toward Wilmington.

Aftermath

Cornwallis occupied the house of Thomas Cooch, and Howe's forces remained at Iron Hill for five days. In a letter to Congress, Washington justified the defeat by saying, "This Morning the Enemy came out with considerable force and three pieces of Artillery, against our Light advanced Corps, and after some pretty smart skirmishing obliged them to retreat, being far inferior in number and without Cannon."

Certain that Howe would advance along the main road toward Wilmington in his bid to capture Philadelphia, Washington continued to fortify the city and the Red Clay Creek. He moved his headquarters from Wilmington to Newport, and the army formed defenses between Newport and Marshallton. While Howe's army remained in place, the two forces engaged in small skirmishes over the next few days.

On September 5, sensing an attack coming, Washington told his troops, "Should they [the British] push their design against Philadelphia, on this route, their all is at stake—they will put the contest on the event of a single battle: If they are overthrown, they are utterly undone—the war is at an end."

On September 7, upon hearing that British ships had left the Chesapeake, Washington was sure Howe's move was imminent. He rallied his troops, referencing Gates's successes against the British in the north. But the attack never came.

On September 8, Howe moved his force north, through Newark and Hockessin into Pennsylvania. Upon realizing what the British were doing late in the night, Washington rushed his forces north as well to find a new defensive position. He settled on Chadds Ford, just across the Delaware border, upon the Brandywine River—the last natural defense before the Schuylkill River and Philadelphia.

It was there that the two armies clashed again in the major Battle of Brandywine on September 11. The British victory in that battle paved the way for their eventual entry into and occupation of the city of Philadelphia.

This success was more than offset by the failure of the expedition to the Hudson, in which Burgoyne surrendered his army after the Battles of Saratoga (First) and (Second). News of Burgoyne's surrender greatly changed the war, because it (and the Battle of Germantown, fought after the British occupied Philadelphia) was a major factor in France's decision to enter the war as an American ally in 1778.