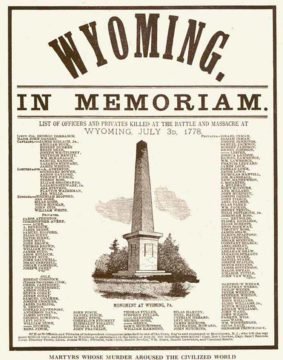

The Battle of Wyomimg Valley (Massacre)

July 3, 1778 at Wyoming, Pennsylvania

Battle Summary

The Battle of Wyoming was also known as the Wyoming Massacre. It was an encounter between American Patriots and Loyalists accompanied by Iroquois raiders that took place in the Wyoming Valley of Pennsylvania.

After the battle, settlers claimed that the Iroquois raiders had hunted and killed fleeing Patriots, before using ritual torture against 30-40 who had surrendered, until they died.

Facts about the Battle of Wyomimg Valley (Massacre)

- Armies - American Forces was commanded by Col. Zebulon Butler and consisted of about 360 Soldiers. British Forces was commanded by Col. John Butler and consisted of about 574 Soldiers and Indians.

- Casualties - American casualties were estimated to be 340 killed and 5-20 captured. British casualties were estimated to be 3 killed and 8 wounded.

- Outcome - The result of the battle was a British-Iriquois victory. The battle was part of the Northern Theater 1778-82.

Prelude

Concerned that the French might attempt to retake parts of New France they had lost in the French and Indian War, the British military adopted a defensive strategy in Quebec. They recruited Loyalists and enlisted Indian allies to conduct a frontier war along the northern and western borders of the Thirteen Colonies.

Colonel John Butler recruited a regiment of Loyalists, while Seneca chiefs Sayenqueraghta and Cornplanter recruited primarily Seneca warriors, and Joseph Brant recruited primarily Mohawks for what became a guerrilla war against the American frontier settlers.

By April, the Seneca were raiding settlements along the Allegheny and Susquehanna Rivers. By early June, the three groups met at the Indian village of Tioga, New York. Butler and the Seneca decided to attack the Wyoming Valley, while Brant and the Mohawks (who had already raided Cobleskill in May) targeted settlements further north.

American military leaders, including General George Washington and Major General Marquis de Lafayette, also sought to recruit Iroquois, primarily as a diversion to keep the British in Quebec busy. These recruitment attempts, however, met with more limited success. The Oneida and Tuscarora were the only tribes of the Six Nations to become Patriot allies.

Battle Begins

On July 2, early in the morning, the British commander sent under a flag of truce, and under escort of an Indian and a Ranger, a message delivered by Daniel Ingersol. Ingersol was not allowed to utter a word out of their hearing to either Colonel Butler or Colonel Denison. Their demand for surrender was refused.

Toward noon, the beating drums down the lower Kingston road, announced the approach of reinforcements from Hanover, with Lazarus Stewart at their head. Lieutenant John Jenkins, Jr. was left in command of the Fort. With him were a few old men including the settlement's minister. Rev. Jacob Johnson's daughter, Lydia, was married to Col. Zebulon Butler. Others at the fort included Capt. Obadiah Gore, Cpt. Wiliam Gallup and Thomas Bennet.

The militia, in the New England way of doing things, met in a sort of town meeting to debate the advantages and disavantages of an immediate attack. They pointed out that Captain Spaulding, with what remained of the companies of Durkee and Ransom, were en route, less than 100 miles away. In a few days, more help might come from Fort Jenkins and even Fort Augusta.

Earlier in the day, Colonel Zebulon Butler had sent Isaac Baldwin with a message to the Board of War at Philadelphia. They hoped for a large group of Continental soldiers within a short time. They argued that the true number of the enemy had not been calculated. There were evidently large numbers of the Seneca.

But, the passionate words of Luzarus Stewart overcame the warnings of the more cautious. His enthusiasm was reinforced by the younger and more adventurous among the group. It has been said that Stewart charged Butler with cowardice; threatening to lead the others against the Indians, if Butler refused to give the order to advance.

On July 3, at 2:00 P.M. some 375 men marched out of Forty Fort to the fife and drum's "St. Patrick's Day in the Morning". It is reported that they carried the "stars and stripes" for the first time. Butler, who was on leave from the Continental Army at the time, led the small army. Colonel Nathan Denison was second-in-command.

The men marched up what is now Wyoming Avenue. They stopped at a bridge which crossed Abraham's Creek. "In fact, Thomas Bennet boldly declared, they were marching into a snare and that they would be destroyed; and he left them at Abraham's Creek and returned to the fort." Another halt was made at Swetland's Hill.

This time scouts reported the enemy was in full retreat. Here Butler, Dorrance and Denison wanted to hold the line until reinforcements arrived from Washington and John Franklin. But Stewart prevailed.

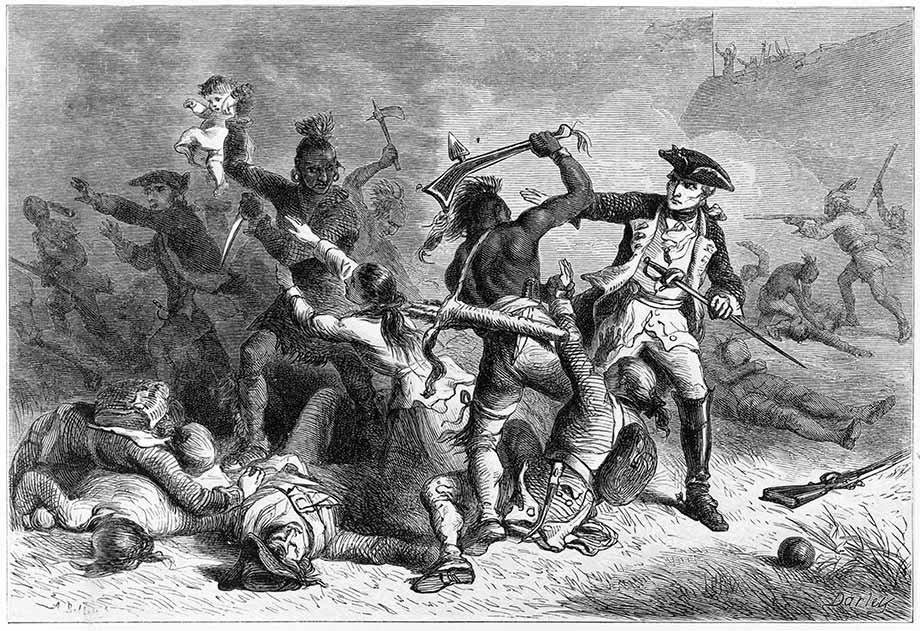

After 4:00 P.M., they marched on toward Exeter flats and defeat. There were only 174, including Butler and Denison, who escaped with their lives. Almost all who were captured were cruelly tortured and killed by the Indians. Samuel Finch managed to survive and later testified to his experience.

When the British Butler saw the colonists forming a battle line, he set fire to Fort Wintermute and ordered the same be done to Fort Jenkins. Upon seeing the thick black smoke, the soldiers believed the enemy were retreating. As Butler had intended, the colonists were deceived and advanced more quickly.

Butler had removed his uniform and the insignia of his rank. He tied a black handkerchief around his head to identify himself, then waited with his Rangers for the battle to begin. The engagement lasted about 30 minutes. The massacre which followed lasted 12 hours, until daybreak the next morning.

The Americans advanced to within 600 feet of the British line when they began to fire. The Rangers remained quietly on the ground until the Americans were within 300 feet of them. The Indians then began to engage the colonists on the right. Captain Hewitt's Company had driven back this group; but not until Lt. Daniel Gore was wounded and Cpt. Robert Drake mortally wounded. The American right advanced more rapidly.

The Rangers rose from the ground soon after the Indians began the attack on the American left. The Rangers withdrew a short distance and returned fire. The colonists mistook this for retreat. It was for this reason that the right got some thirty rods in front of the left. The soldiers to the left, in closest contact with the swamp, were suddenly attacked by the Senecas.

Outflanked, Denison ordered Cpt. Whittlesey to wheel back and form an angle to the main line. He hoped this would protect the left flank. "The western line was rolled up, and forced back on the center by the Indians in the rear; and the farmer boys, unaccustomed to the blood curdling yelps of the savage warriors, were thrown into an indescribable confusion and panic."

The officers commands had been mistaken for the order to retreat. The fleeing soldiers of the left wing took with them the center as well as the right wing. Col. Dorrance tried to stop the panic, but was shot down and captured.

Neither Butler nor Denison could stop the flight of their men. Garrett was killed and Hewitt held his part of the line. His men made a slight retreat and returned fire. Seeing the panic by the other line, an officer is quoted as telling Hewitt "The day is lost, see the Indians are sixty rods in our rear, shall we retreat"---"I'll be damned if I do" was his answer. "Drummer strike up," he cried, as he vainly strove to rally his men.

Just then a bullet struck him dead, and the last of the crumbling line gave way in a pandemonium of flight. Reports from those who survived indicate that few men were killed in the actual battle.

Aftermath

Butler claimed that his force took 227 scalps, burned 1,000 houses, and drove off 1,000 cattle plus many sheep and hogs. The Seneca Indians were angered from the accusations of atrocities they said they had not committed, and at the militia taking arms after being paroled. Later that year, Joseph Brant, under the command of Butler, further retaliated in the Cherry Valley massacre.

Reports of the massacres of prisoners and atrocities at Wyoming infuriated the American public. Afterward, Colonel Thomas Hartley arrived with his additional Continental Regiment to defend the valley to try to harvest the crops. They were joined by a few militia companies, including that of Denison, who violated his parole to join the force.

In September, Hartley and Denison ascended the east branch of the Susquehanna with 130 soldiers, destroying Indian villages as far as Tioga and recovering a large amount of plunder taken during the raid. They skirmished with the hostile Indians and withdrew when they learned that Joseph Brant was assembling a large force at Unadilla.