The Battle of Stoney Point

July 16, 1779 at Stony Point, New York

Battle Summary

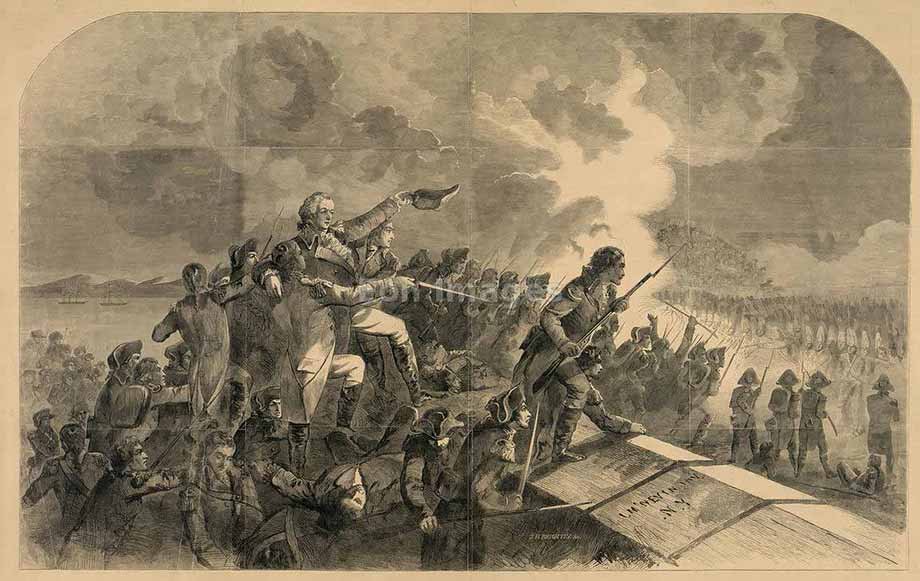

In a well planned and executed nighttime attack, a highly trained select group of General George Washington's Continental Army troops under the command of Brigadier General Anthony Wayne defeated British troops in quick and daring assault on their outpost in Stony Point, New York, approximately 30 miles north of New York City.

The British suffered heavy losses in a battle that served as an important victory in terms of morale for the Continental Army. While the fort was ordered evacuated quickly after the battle by Washington, this key crossing site was used later in the war by units of the Continental Army to cross the Hudson River on their way to victory over the British.

Facts about the Battle of Stoney Point

- Armies - American Forces was commanded by Brig. Gen. Anthony Wayne and consisted of about 1,350 Soldiers. British Forces was commanded by Gen. William Howe and consisted of about 700 Soldiers.

- Casualties - American casualties were estimated to be 15 killed and 83 wounded. British casualties was approximately 20 killed, 74 wounded, 58 missing, and 472 captured.

- Outcome - The result of the battle was an American victory. The battle was part of the Northern Theater 1778-82.

Prelude

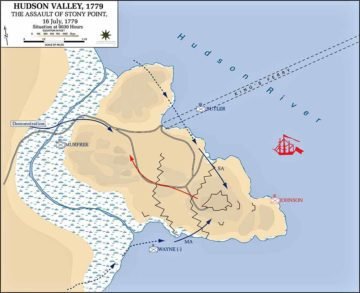

Stony Point has a rocky promontory and wooded faces, it rose 150 feet at its highest point and it projected out into the Hudson River for more than 1/2 mile. The westerly, or inland slope, dropped off into a marsh. King's Ferry landing was at the north side and was submerged in deep water. The south side was also covered with water.

The British fortified Stoney Point with 7 or 8 detached batteries on the uneven summit and converted the west end rock formation into a strong bastion. They had also cut down all the surrounding woods and used the felled trees to construct 2 rows of abatis from water to water across the point.

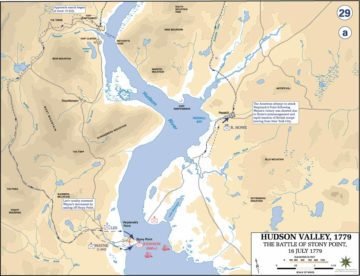

To protect the main British garrison stationed in New York City and dissuade Washington from moving his army down the Hudson River from his encampment at West Point, Lieutenant General Henry Clinton established and maintained an outer network of defenses. An integral part of this defensive network included several strongholds along the river. Two of the strongest were at Stoney Point, 24 miles north of New York City, and Fort Lafayette on Verplank's Point.

The gunboat, HMS Vulture, cover both of the forts from the water. Verplank's Point, across the river, could be signaled by rocket for reinforcements.

Stony Point had a 625-man garrison, commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Henry Johnson. Its defenses consisted of two landside lines and outposts protected by obstructions that made an approach from the west difficult. The outer line had 300 men and 7 guns and the inner line had 300 men and 6 guns. Johnson felt certain that his defenses were secure. The British had established control of this region and had nicknamed Stony Point its "little Gibraltar."

Washington responded to Clinton's move by marching his troops north from Middlebrook, New Jersey, to protect the American fortifications at West Point. Clinton garrisoned Stony Point and Verplank's Point with about 1,000 men to protect the King's Ferry, which crossed the Hudson River between the two points. He then launched raids against Connecticut coastal towns, in the continuing attempt to lure Washington into battle.

On June 15, Washington had ordered militia Captain Allen McLane to gather information on the British strength at Stoney Point. Two weeks later, McLane entered the place disguised as a local female farmer. He told the British guards that she was visiting her sons inside the fort. He found out that the works were still unfinished and vulnerable. He also conducted further reconnaissance on the outside of the fort.

On July 2 , Washington observed the British works himself from nearby Buckberg Mountain and devised a plan. Wayne would lead a surprise midnight assault against Stony Point. Wayne considered this surprise attack as a revenge for the Battle of Paoli. He commanded the Corps of Light Infantry, a select force which probed British lines, fought running skirmishes, and defended the army against sudden attack.

Battle Begins

On July 15, after a morning muster, the Corps of Light Infantry marched from Sandy Beach north of Fort Montgomery beginning at noon. Any civilians met along the route of march were to be taken into custody to prevent them from warning the British. The column, often forced to march single file over rough terrain and roads, took a circuitous route west through Queensboro to the west and over Dunderberg Mountain to avoid detection by the British. The Corps began arriving at 8:00 PM at the Springsteel farm, a mile and a half west of the fortifications, and by 10:00 PM had been formed in the attack columns.

The men were given a rum ration and their orders. They were also given pieces of white paper to pin to their hats in order to help them tell each other from the British in the darkness. The columns then moved out at 11:30 PM. to their jump-off points, diverging immediately, to begin the assault at midnight. These attack columns were led by groups of volunteer soldiers nicknamed the “forlorn hope” who were responsible for breaking holes in enemy defenses and along with their weapons, were armed with axes and picks.

Bad weather that night aided the Continentals. Cloud cover cut off moonlight and high winds forced the British ships in Haverstraw Bay to leave their posts off Stony Point and move downriver. At midnight, the attack began with the columns crossing the swampy flanks of the point. The southern column unexpectedly found its approach inundated in 2-4 feet of water and required 30 minutes to wade to the first line of abatis, during which it and Murfree's demonstration force were spotted by British sentries and fired upon.

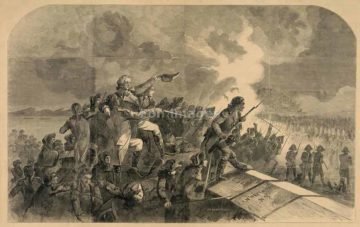

Under fire, Wayne's column succeeded in getting inside the British first line of defenses. Wayne himself was struck in the head by a spent musket ball and fell to the ground, leaving Colonel Febiger to take over command of Wayne's column. Meanwhile, Butler's column had succeeded in cutting its way through the abatis. The two columns penetrated the British line almost simultaneously and seized the summit when six companies of the 17th Regiment of Foot took positions opposite the diversionary attack and were cut off.

Because of the stealth in which the Patriot assault forces approached the British defenses on the slopes of the hill, the artillery pieces that the British had placed on the summit for just such defensive purposes were unsuccessful in repelling the attack. Due to the speed at which the Patriots were moving, the British cannons could not be lowered to an angle low enough to sufficiently harass the men assaulting up the hill.

The first man into the British upper works was Lieutenant Colonel Francois de Fleury, a French engineer commanding a battalion of the 1st Regiment. As the men entered the British works they called out, "The fort's our own!" – the prearranged watchword to distinguish friend from foe. The action lasted 25 minutes and was over by 1:00 AM.

Before dawn, Wayne sent a brief dispatch telling Washington, "The fort and garrison, with Colonel Johnston, are ours. Our officers and men behaved like men who are determined to be free." The next day, Washington rode into the works to inspect the battlefield and congratulate the troops.

Aftermath

While the strategic value of capturing Stony Point was up for debate, it was regardless a huge victory for morale for the Continental Army. Its minimal strategic value was that it asserted Washington's foothold on the nearby West Point.

Washington's instructions to Wayne had allowed for the possibility of an assault on Verplanck's Point once Stony Point was taken. As part of the attack on Stony Point, Washington had directed two brigades to begin moving toward Verplanck's, and dispatched Colonel Rufus Putnam with a small force to divert the attention of its British garrison. Putnam was able to begin diversionary fire against Verplanck's shortly after the assault on Stony Point began, and he successfully distracted the British until morning.

On July 16, in the morning, Wayne's forces turned Stony Point's cannons against Verplanck's, but the fire at long range did no significant damage. The fire was sufficient, however, to prompt the Vulture to cut her anchor and drift downstream.

On July 17, Washington then sent Major General Robert Howe to lead the two brigades to besiege Verplanck's Point, but the force was not provisioned with adequate artillery or siege equipment, and could do little more than blockade the fort.

On July 18, some British troops were landed from ships sent upriver, and more were rumored to be coming overland, so Howe decided to withdraw.

Washington had not intended to hold either point, and Stony Point was abandoned by the Americans on July 18, after carrying off the captured cannons and supplies. The British briefly reoccupied the site only to abandon it in October, as General Henry Clinton prepared a major expedition to the southern states.

Some of the captured officers were exchanged immediately after the battle, but the more than 400 prisoners of other ranks were marched off to a prison camp at Easton, Pennsylvania.

Contemporary Patriot accounts note that Wayne had given quarter to the garrison of Stony Point despite the alleged treatment of his own men at the "Paoli Massacre" in 1777. British reports also remarked that unanticipated clemency was immediately shown the garrison. Because of the relative ease with which the Continental Army took over the fort however, the British commander of Stony Point, Colonel Johnson, was court martialed in New York City with accusations against him of inadequate defense.