The Battle of Pell's Point

October 18, 1776 at Eastchester, New York

Battle Summary

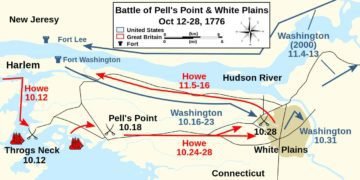

On October 12, British forces landed at Throgs Neck in order to execute a flanking maneuver that would trap General George Washington and the main body of the Continental Army on the island of Manhattan. The Americans thwarted the landing, and General William Howe looked for another location along Long Island Sound to disembark his troops.

On October 18, Howe landed 4,000 men at Pelham, three miles north of Throgs Neck. Inland, there were 750 men under the command of Colonel John Glover. He positioned his troops behind a series of stone walls and attacked the British advance units. As the British overran each position, the American troops fell back and reorganized behind the next wall. After several such attacks, the British broke off, and the Americans retreated.

The battle delayed British movements long enough for Washington to move the main army to White Plains and avoid being surrounded on Manhattan. After losing to the British in a Battle at White Plains, and losing Fort Washington, Washington retreated across New Jersey to Pennsylvania.

Facts about the Battle of Pell's Point

- Armies - American Forces was commanded by Col. John Glover and consisted of about 840 Continentals. British Forces was commanded by Gen. William Howe and consisted of about 4,000 Soldiers.

- Casualties - American casualties were estimated to be 8 killed and 13 wounded. British casualties was approximately 5 killed and 20 wounded.

- Outcome - The result of the battle was a tactical British victory with a strategic American retreat. The battle was part of the New York and New Jersey Campaign 1776-77.

Prelude

On October 12, leaving behind three brigades under the command of Lord Hugh Percy on Manhattan Island, Howe embarked his main army in 80 vessels and proceeded up the East River, through Hell Gate, and landed at Throgs Neck. Throgs Neck is a narrow spit of land that sits between the East River and Long Island Sound.

Howe had decided against a frontal attack against the American forces at Harlem Heights and Fort Washington, and chose instead to attempt a flanking maneuver. Conveniently for Howe, there was a road running from Throgs Neck to Kingsbridge, directly behind the American forces. He hoped to use this road to flank the Americans and pin them against the Hudson River.

Under the cover of fog, an advance force of 4,000 British, under the command of General Henry Clinton, was landed on Throgs Neck. To their dismay, they found they were not on a peninsula, but on an island, separated from the mainland by a creek and a marsh. There were two ways to get to the mainland: a causeway and bridge at the lower end, and a ford at the other.

The Americans were guarding both ways. Colonel Edward Hand and a detachment of 25 men from the 1st Pennsylvania Regiment positioned themselves behind a length of cordwood along the causeway. They surprised the British troops, who fell back and made an attempt to cross at the ford, which was guarded by another American detachment.

The Americans guarding both positions were quickly reinforced, and the defenders soon numbered over 1,800 men. Howe decided it would be better to retreat and land somewhere else. He made camp on Throgs Neck and remained there for six days while supplies and reinforcements, including 7,000 Hessian soldiers under the command of Major General Wilhelm von Knyphausen, were brought up from New York.

By October 17, the Continental Army was on its way to White Plains, leaving behind 2,000 men to garrison Fort Washington.

On October 18, just after midnight, Howe embarked his army again and decided to land a few miles to the north at Pell's Point, near the town of Pelham. After hearing of the landing on Throgs Neck, Washington knew he risked entrapment on Manhattan. He made the decision to move his army to White Plains, where he believed they would be safe. From his position near Eastchester, about a mile from Pell's Point, Colonel John Glover was commanding a 750-man brigade with support from 3 cannon.

Battle Begins

On October 18, at dawn, the British began to land on the shore, Clinton's advance guard of 4,000 British light infantry and Hessians landing first. Inland, opposing them, was a brigade of some 750 men under the command of Glover. Glover was atop a hill with a telescope when he noticed the British ships. He sent Major William Lee to report to Major General Charles Lee, Washington's second in command, and ask for orders. However, Lee did not give any orders, and in the absence of orders Glover chose to attack.

Glover turned out his brigade, which consisted of the 14th, 13th, 3rd and the 26th Continental Regiments. Glover left the 150 men of the 14th Continentals behind in reserve. He had not closed half the distance when he ran into approximately 30 British skirmishers. Glover ordered a Captain and his 40-man company forward as an advance guard to hold the British in check, while Glover organized the rest of the force.

Glover prepared an ambush by placing the main body in staggered positions behind the stone walls that lined either side of the laneway leading from the beachhead to the interior. He instructed each of the regiments to hold their position as long as they could and then to fall back to a position in the rear, while the next unit took up the fighting. He then rode up to take command of the advance guard.

The American advance guard and the British began to engage each other. After a little while, the British were reinforced, and Glover ordered a retreat, which was done without confusion. The British troops began to advance at the retreating Americans. However, the 200 soldiers of the 13th Continentals, that were stationed behind the stone wall, stood up and fired at the British when there were only 30 yards away. The ambush worked, and the column of British troops took heavy losses and fell back to the main body of the invading army.

The British waited 30 minutes before attacking again. This time they attacked with all 4,000 men and 7 cannon. The British bombarded the American position behind the stone wall as their infantry advanced.

The cannon fire was ineffective, and when the British were 50 yards away the Americans fired a volley which stopped the British infantry. The British returned fire, and the fight ensued for 20 minutes, at which point the lead American regiment fell back under cover of the next reserve regiment. The 3rd Continental Regiment was stationed behind the stone wall on the opposite side of the road.

The British attacked the position of the 3rd Continentals, and an engagement ensued. Both sides kept up constant fire, the Americans breaking the British lines several times. However, after 17 volleys, the British numbers began to overwhelm the Americans, and Glover ordered a withdrawal to another stone wall on the crest of a hill while the next regiment in line, the 26th Continentals, engaged the British.

A reconnaissance party of 30 men was sent out from behind the third stone wall to see if the British would try and flank the American position. The party ran into the British, which had continued to advance, and they fell back to the stone wall. The Americans behind the wall fired one volley before Glover gave the order to retreat.

The Americans retreated across a bridge over the Hutchinson stream. Their retreat was covered by the 150 men of the 14th Continentals, who engaged in an artillery duel with the British. Howe, camped on a hill on the opposite side of the stream, but made no attempt to cross the stream.

Aftermath

With the British advance delayed, the main American army under Washington was able to safely evacuate from Harlem Heights to White Plains. Howe slowly moved his army through New Rochelle and Scarsdale.

On October 28, Howe sent 13,000 men to attack the Americans, resulting in a minor victory over Washington at the Battle of White Plains. Fort Washington, the last American stronghold on Manhattan, fell on November 16. With these defeats, Washington and his army retreated across New Jersey and into Pennsylvania, paving the way for the battles of Trenton and Princeton.