The Siege of Boston

May 17, 1775- March 17, 1776 at Boston, Massachusetts

Boston was the American headquarters of the British army in 1775 led by General Thomas Gage, he was commander-in-chief of British troops in North America. General Gage was also appointed governor of Massachusetts and was instructed by King George’s government to enforce royal authority in the troublesome colony.

British Troops occupied most of the city, while the navy blockaded its port. General Gage commanded four regiments of British regulars (about 4,000 men) from his headquarters in Boston, but the countryside was largely controlled by Patriots and their sympathizers.

Facts about the Siege of Boston

- Armies – American Forces was commanded by Gen. George Washington and consisted of between 6,000 to 16,000 Colonial militiamen. British Forces was commanded by Gen. William Howe and consisted of between 4,000 to 11,000 Soldiers.

- Casualties – American casualties were estimated to be 19 killed or wounded. British casualties was approximately 60 killed or wounded and 35 captured. The Siege was part of the Boston campaign, 1774-76

- Outcome – The result of the Siege of Boston was a strategic American victory which resulted in the end of the eight-year British occupation of Boston. British troops evacuated the town and sailed to the safety of Nova Scotia, a British colony in Canada.

The Siege of Boston Begins April 1775

Boston is Surrounded

Following the battles of Lexington and Concord, all the New England colonies, along with the Southern colonies soon after, raised militia units to send to Boston immediately. Thousands of colonial militiamen surrounded Boston in an effort to contain the British troops there. However, because the British maintained control of Boston Harbor, they were able to receive additional soldiers and supplies.

Over the next few days, more militiamen arrived from further afield, including companies from New Hampshire, Connecticut, and Rhode Island. Artemas Ward took command of the militiamen and they surrounded the city, blocking its land approaches and putting the occupied Boston under siege.

British army fortifies Boston

In the meantime, The Massachusetts militia, under William Heath’s command, built a siege line around the Boston and Charlestown peninsulas that extended from Chelsea to Roxbury.

The British, under command of General Thomas Gage, ordered lines of defenses with ten twenty-four pound guns at Roxbury. They also fortified the high ground in Boston proper. In a strategic blunder, General Thomas Gage moved the forces from Charlestown to Boston, basically abandoning Charlestown. This left Charlestown, Bunker Hill, Breed’s Hill, and Dorchester heights undefended.

During the Siege many patriot residents moved out of Boston, and some Loyalists, fearing that they were no longer safe, from the surrounding countryside moved into town. Conditions within the town were harsh for all who remained; although the British maintained control of Boston Harbor, provisions dwindled while they waited for supply ships to arrive.

Lack of Supplies

While the Royal Navy were able to resupply the city from Nova Scotia, among other locations, supplies in Boston were short. American privateers were able to harass any supply ships however.

Admiral Samuel Graves authorized the Royal Navy and Loyalist merchant ships to acquire supplies and other building materials. These coastal communities and local militias rose up and resisted the British.

Their resistance of the coastal communities led Admiral Samuel Graves to authorize a reprisal in October. This resulted in the Burning of Falmouth. This act sparked outrage in the colonies and contributed to the passing of legislation by the Second Continental Congress that established the Continental Navy.

On May 3, 1775 the Massachusetts Provincial Congress authorized Benedict Arnold to raise forces to raid Fort Ticonderoga in order to acquire its heavy weapons.

Under the joint leadership of Benedict Arnold and Ethan Allen, a Connecticut militia company captured both Fort Ticonderoga and Fort Crown Point. Along with capturing the forts, they also captured a large military vessel on Lake Champlain when they were raiding Fort Saint-Jean in Canada.

They recovered more than 180 cannons, along with other weapons and supplies that would prove useful for the Continental Army to break the Siege of Boston.

On May 21, General Thomas Gage sent troops out to some of the islands in Boston Harbor to raid farmers for supplies. This did not go unnoticed, and the militia attacked the British raiding party on Grape Island. The militia drove off the British and managed to destroy 80 tons of hay when they set fire to the island’s barn.

On May 27-28,1775, the colonials began clearing the other islands in Boston Harbor of supplies useful to the British. The British attempted to stop the removal any livestock or supplies by the Continentals and this led to the Battle of Chelsea Creek.

The Battle of Chelsea Creek resulted in American victory. The British losses consisted of two British soldiers killed and the British ship Diana destroyed.

A secret committee of Congress had been appointed, with ample powers to lay in a stock of this necessary article. Some swift-sailing vessels had been dispatched to the coast of Africa to purchase what could be procured; a party from Charleston forcibly took about 17,000 pounds of gunpowder from a vessel near the bar of St. Augustine.

Some time later, Commodore Hopkins stripped Providence, one of the Bahama Islands, of a number of artillery and stores; but the whole, procured from all these quarters, was far short of what was needed.

In order to supply the Colonial army ,besieging Boston, with the necessary means of defense, a request for firearms was made to Massachusetts, but on a closer look, it their public stores afforded only 200 arms. Orders were issued to purchase firearms from private people. Few people had any to sell and fewer would part with them.

The colonial army also had issues with supply, and with command. Its diverse militias needed to be organized, fed, clothed, and armed, and command needed to be coordinated, as each militia leader was responsible to his home states province’s congress.

Creation of the Continental Army

George Washington accepting his Continental Army commission as commander-in-chief, from the Second Continental Congress June 15, 1775

The Second Continental Congress, in response to the confusion over command in the camps there, and in response to the capture of Fort Ticonderoga on May 10th, the need for organized professional full time army became clear.

In May, The Colonial and Provincial militia troops, who answered the alarm on 19 April 1775 were initially called the New England Army Under the command of Artemas Ward.

On May 26, Congress officially adopted the the New England Army outside Boston as the Continental Army.

On June 15, the Second Continental Congress named George Washington its commander-in-chief of the newly formed the Continental Army. Washington was charged with forming these companies into an army and directing the siege of Boston.

On June 21, General Washington left Philadelphia for Boston, but did not learn of the action at Bunker Hill until he reached New York City.

British Attack Bunker Hill

On May 25, Generals John Burgoyne, Henry Clinton, and William Howe arrived in Boston, along with about 2,000 reinforcements, on the HMS Cerberus.

On June 12, General Gage finalized a plan to break out of Boston. The plan was to reoccupy and fortify Bunker Hill along with Dorchester Heights, which the British had abandoned in April, on June 18.

On June 15, the Committee of Safety, which took control of the colonies away from royal officials, learned of these plans and decided that additional defensive steps were necessary. They instructed General Artemas Ward to fortify both Bunker Hill and the heights around Charlestown.

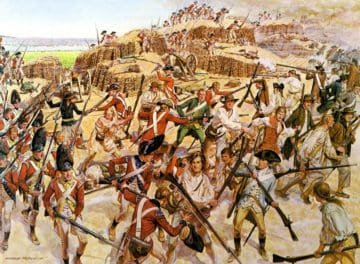

On June 16, colonial militiamen under command of Colonel William Prescott built fortifications on top of Breed’s Hill. The militiamen had originally been ordered to r fortify Bunker Hill but instead chose the smaller Breed’s Hill, because it was closer to Boston.

On June 17, British troops, under the command of Major General William Howe and Brigadier General Robert Pigot, attacked the Americans at Breed’s Hill and and the Charlestown Peninsula fell back under British control. Although British defeated the colonial militiamen but was only was technically a British victory.

The British lost about a third the troops killed or wounded, including 19 British Officers, a significant portion of the entire British officer corps in all of North America. Losses were so heavy that the attack was not followed up. The siege was not broken, and in September General Gage was recalled to England and replaced by General Howe as the British commander-in-chief.

Despite their loss, the inexperienced and outnumbered colonial forces inflicted significant casualties against the enemy, and the battle provided the Colonial Army with an important confidence boost.

The Siege of Boston turns into a Stalemate

After the Battle of Bunker Hill, the Siege of Boston turned into a stalemate for a number of months.

On July 2, General George Washington arrived in Cambridge, Massachusetts and took command of the newly established Continental army. He set up camp at Harvard College in the home of Benjamin Wadsworth.

General Washington soon determined that its size had been reduced from about 20,000 men to about 13,000 men fit for duty. Also the battle of Bunker Hill had severely depleted the army’s powder stock.

By the end of July, forces and supplies were beginning to arrive. Companies of riflemen around 2,000 men, from Maryland, Pennsylvania, and Virginia joined the Continental Army in Boston. But British also were busy bringing in reinforcements as well. By the time of Washington’s arrival the reinforcements had increased the number of British troops in Boston more than 10,000 men.

Soon after General George Washington took command, he started working on combining the many various militias to more closely resemble an army. General George Washington appointed senior officers and introduced more organization and discipline to the militiamen.

Officers of different ranks were required to wear different uniforms to more easily be distinguished from those below and superior to them.

On July 16, General George Washington moved his headquarters from the Benjamin Wadsworth House to the John Vassall House, later Henry Wadsworth Longfellow House.

Throughout the summer and fall of 1775, Washington ordered the improving of defenses. Trenches in Boston Neck were dug up to extend towards Boston. Both sides dug in but neither side chose to take any significant action, but skirmishes occasionally did break out.

On July 30, the British burned a few homes in Roxbury as they pushed back an American advanced guard.

In August, General George Washington sent about 1,200 men to Charlestown Neck to dig entrenchments on the hill. Even with a British bombardment, they were successfully able to dig the trenches.

On August 2, an American soldier was killed and the British hung up his body by the neck. In response, other American troops marched up to the British lines and attacked. they continued sharp shooting at the British all day, wounding many.

On August 30, British troops attempted a surprise breakout was made from the Boston Neck when they set fire to a tavern and afterwards withdrew their defenses. That night, 300 American troops attacked and burned the lighthouse on Lighthouse Island, killing several British troops and also capturing twenty-three others with only losing one of their own.

In early September, General George Washington began drawing up plans for a two pronged attack. The First was he would dispatch 1,000 men to invade Quebec from Boston and secondly they would launch an attack on Boston.

General Washington had also authorized appropriating and outfitting local fishing vessels to gather intelligence and British supplies. This type of activity later helped form into the Continental Navy, which would later be established after the British Burning of Falmouth in October of 1775. The provincial assemblies of both Connecticut and Rhode Island agreed and started to arm ships and authorize privateering.

The Second Continental Congress was also seeking to take some action and to capitalize on the capture of Fort Ticonderoga back in May, and authorized General George Washington’s planned invasion of Canada. The Americans first sent several letters to the inhabitants of Canada but were ultimately rejected by the French-speaking British colonists there.

On September 11, Benedict Arnold was put in command of about 1,100 men, drawn from the army assembled outside Boston, and left on an expedition through the wilderness of Maine to attack Quebec.

In Boston, General George Washington summoned a council of war to create a plan for an all out assault on Boston. The plan was to send troops across Black Bay about fifty at a time in flat bottomed boats. General Washington believed that to keep all the men together upon the arrival of winter would be very difficult. In the end, his plan was unanimously rejected by the war council anyway.

In early November, around 400 British soldiers went on a raiding expedition to Lechmere’s Point in hopes of capturing livestock. Colonial soldiers, that had been sent to defend the point, skirmished with the British raiding party. The British soldiers suffered two killed, but they were able to acquire 10 cattle.

On November 29, Colonial Captain John Manley, commander of the schooner Lee, captured a British brigantine, HMS Nancy, outside Boston Harbor. This ship turned out to be one of the most valuable items captured during the Siege of Boston. The British ship had been carrying a large supply of military stores and ordnance for the British.

General Washington’s ultimate goal was to drive the British from Boston, and in order to do this, his army required weapons.

In late November, Henry Knox suggested the idea to Washington, to retrieve all the cannon that had recently been captured at the fall of forts Ticonderoga and Crown Point in upstate New York, and used them in the Siege of Boston.

General Washington agreed and sent an expedition, commanded by Colonel Henry Knox, to transport more than 60 tons of captured military supplies from New York’s Fort Ticonderoga back to Boston.

On December 5, Colonel Henry Knox arrived at Fort Ticonderoga. Colonel Henry Knox then began what came to be known as “the noble train of artillery”, hauling by ox-drawn sled 60 tons of cannon and other armaments across some 300 miles of ice-covered rivers and snow-draped Berkshire Mountains to the siege of Boston camps.

On several occasions cannon crashed through the ice on river crossings, but the detail’s men were always able to recover them. In the end, what Henry Knox had expected to take just two weeks actually took more than six weeks.

Both sides faced crisis toward the end of 1775

British

For the British army at Boston were suffering the effects of the naval blockade, food and wood was in short supply, as well. It had become very difficult to supply the city because of winter storms and the many rebel privateers.

The need for fuel was particularly felt in a climate where the winter is both severe and tedious. Their supplies from Britain did not reach Boston for for some time after they were expected. Several were taken by the American cruisers, and others were lost at sea, including many of the British coal-ships.

They resorted to the destruction of nearby houses, which they pulled down and used the lumber from them to burn and keep warm. Vessels were dispatched to the West Indies to procure provisions.

The British troops were preparing to desert from constant hunger. On top of all that, scurvy and smallpox had broken out in Boston.

American

For the Americans besieging Boston, gunpowder was in short supply. Also many of the American soldiers went unpaid throughout the war and most of their enlistments expired at the end of 1775. Washington many problems were made worse by his soldiers from rural communities that was being exposed to smallpox. He moved the infected troops to a separate hospital to help contain the problem.

Another major issue for General George Washington was that the American army was only a temporary army. Most of the troops in the army had enlistments expired on December 31, 1775. General Washington introduced a number of recruitment incentives and was able to keep the army sufficiently large to maintain the siege, although it was by then smaller than the besieged British garrison in Boston.

On the last day of the year 1775 the whole American army amounted to no more than 9,650 men. Of the remarkable events during the year 1775, it was not the least that one army was disbanded and another enlisted, all within musket-shot of 20 British regiments.

In mid-January, on orders from London, British Major General Henry Clinton sent Armed ships and transports to the Carolina’s and Georgia with about 1,500 men. The objective of this was to join forces with additional troops on their way from Europe and to then take a port in Georgia with the purpose of procuring some rice.

But the Georgia’s citizens, with the aid of a militia from South Carolina, so effectually resisted them that of the 11 British ships sent, only 2 ships safely got off with their cargoes.

It was not until the British garrison’s supplies was nearly exhausted that the British transports entered Boston’s port and relieved the garrison.

Americans Fortify Dorchester Heights

On January 27, 1776, after a challenging journey across snowy terrain, “the noble train of artillery” arrived in in Cambridge. Colonel Henry Knox was finally able to report the arrival of the weapons train, including 59 cannon, to General Washington. While the attack on Quebec failed, Colonel Henry Knox accomplished “one of the most stupendous feats of logistics” of the entire war.

In early February, several farmhouses were then burned in Dorchester by a British raiding party. There were still at least 2,000 Colonial militiamen who did not have any weapons. Powder was still scarce and yet daily requests were made for the small amounts which was on hand for the defense of the various parts threatened with upcoming British breakout.

On February 28, A proposal was made to take possession of Dorchester Heights. Some of the cannon were placed in fortifications around Boston. To conceal this plan and to divert the attention of the British garrison, a bombardment of the town from other directions was to take place.

On March 2, under Colonel Knox’s direction, the American troops began placing some of the cannons from Fort Ticonderoga and began bombarding the city. In response, the British responded with their own cannons. The Americans continued to exchange fire with the British for two days.

Little damage was done to either side. A few houses were damaged and some British soldiers in Boston were killed as well.

On the night of March 4, General Washington moved more of the Fort Ticonderoga cannons and several thousand of his men to occupy Dorchester Heights overnight. American troops began placing some of the cannons from Fort Ticonderoga, on Dorchester Heights. Dorchester Heights overlooks Boston and it harbor.

A covering party of about 800 men led the way. These were followed by the carts with the intrenching tools, and 1,200 man working-party, commanded by Gen. Thomas. In the rear there were more than 200 carts loaded with fascines and hay in bundles.

While the other cannon positions were bombarding Boston, the 1,200 man working-party worked in silence. Digging trenches was impractical due to the frozen ground, so Washington’s men used logs, branches, and anything else they could find to fortify their position overnight instead.

The work party finished their defensive lines by morning. The difference between Dorchester Heights that evening and the morning of March 5 took the British high command completely by surprise.

On March 5, the British commanders awoke to heavy cannons overlooking Boston and its harbor. The British started a two-hour cannon barrage at Dorchester Heights immediately after, though this had no effect because the American guns were too high for the British to reach.

They knew the British situation had become untenable. Gen. William Howe was told that if the Americans kept possession of these heights he would not be able to keep one of his majesty’s ships in the harbor.

Howe and his officers agreed that if they were to hold Boston, they must remove the colonists from the heights right after the barrage. General Howe planned an attack to reclaim the high ground, but it never went through due to a snow storm.

British General William Howe realized his troops could not defend the town against the Continental army’s elevated position at Dorchester Heights, and soon decided to evacuate instead.

The Siege of Boston ends

On March 8, The citizens of Boston sent a letter to General Washington, they feared that the city would be destroyed from the British. General Washington formally rejected the letter because it had not been addressed to him by name or title. The letter did have the intended effect though. Upon the beginning of the evacuation, the British departure was unable to be hindered by any American fire.

On March 9, the British opened a massive fire barrage that lasted through the night, after seeing movement on Dorchester on Nook’s Hill. Four men were killed with one cannonball, but no other damage was done. The following day, the colonists collected about 700 cannonballs the British had fired at them.

On March 10, General Howe issued a proclamation that ordered the citizens of Boston to give up any linen and woolen goods that the colonists might could use to continue the war.

Loyalist Crean Brush, Esq. was authorized to receive these goods and in return he gave worthless certificates. Shops were opened and stripped of their goods. A licentious plundering took place. Much was carried off, and more was wantonly destroyed.

The looting was forbidden in the orders, and the guilty threatened with death, but nevertheless every conceivable mischief one could suggest was committed.

Over the course of the next week, the British fleet sat in Boston harbor waiting for favorable winds. British soldiers and Loyalists were being loaded onto the ships as they waited.

Meanwhile, the Americans successfully conducted naval activities in the Boston harbor and were able to diverted many British supply ships to ports under Colonist control.

On March 15, the winds turned favorable, but before the British could leave, the winds turned against them again.

British Evacuate Boston

On March 17, the wind became favorable again. The troops were given permission to burn the town in case of any disturbances as they marched to their ships. The British, amounting to more than 7,000 troop, left their barracks standing, and also a number of cannon spiked, 4 large iron seamortars, and stores to the value of 30,000 pounds. They had demolished the castle, and knocked off the trunnions of the cannon there.

The British began moving out by 4:00 a.m. and all ships were underway five hours later at 9:00 a.m. 120 ships with over 11,000 people aboard departed Boston. Thedestination was temporary refuge in Halifax, Nova Scotia, a British colony in Canada. Of these passengers, 9,906 were men with 667 women and 553 children.

On March 18, Washington marched into Boston, but there was little time for rejoicing. As Americans moved to begin reclaiming Boston and Charlestown after the British fleet left the harbor, they believed the British to still be on Bunker Hill, but they realized that those were just dummies left behind.

Because they ran the risk of coming in contact with smallpox, only men with previous exposure to the disease entered Boston under Artemas Ward’s command.

On March 20, with the risk of disease was lower, more colonials entered the city.

General Washington wanted to make sure that the British’s departure of the harbor wasn’t too easy. Captain Manley was directed to harass the departing fleet and was somewhat successful, capturing the ship that carried Crean Brush and the goods he had collected before their departure.

General Howe left a small amount of ships to intercept any incoming British vessels. They successfully redirected many ships carrying British troops to Halifax instead of Boston. When some unsuspecting troops, not knowing that Boston had been evacuated, landed in Boston, they found themselves captured by the Americans.

Aftermath

The inhabitants, released from the harsh conditions of a siege life, and from the poor treatment to which they were subjected, hailed General Washington as their deliverer.

Congratulations between those who had been confined within the British lines during the Siege of Boston, and those who were excluded from entering them, were exchanged with an enthusiasm which cannot be described. Washington was honored by Congress with a vote of thanks.

The Massachusetts council and House of Representatives praised General Washington in a joint address, in which they expressed their good wishes in the following words:

“May you still go on approved by Heaven, revered by all good men, and dreaded by those tyrants who claim their fellowmen as their property.”

The British senior military leaders, of the Boston campaign, were criticized for their actions. For his failures during the Siege of Boston, General Howe was greatly criticized in both British press and Parliament, though he remained in command for two more years to come and led the New York and New Jersey Campaign and the Philadelphia Campaign.

General Gage was never given another combat command and General Burgoyne saw action in the Saratoga Campaign that ultimately led to his capture. General Clinton commanded the British forces after Howe from 1778-1782 when the war ended.

Many Loyalists in Massachusetts left with the British. Some went to rebuild their lives in England and some returned to America following the war. Most stayed in Nova Scotia and settled in places like Saint John.

Boston ceased to be a military target after the siege. It did continue to be a focal point for many activities during the war though. Its port was an important point for fitting war ships and privateers.

General Washington knew there was little time for rejoicing. He rightly suspected that the British would head for New York City.

In April, the local militias disbanded and went to back their homes. General Washington took most of the Continental Army to fortify New York City and the start of the New York and New Jersey campaign.

March 17 is now celebrated as “Evacuation Day,” when 11,000 redcoats and hundreds of Loyalists left the city by boat.