The Saratoga Campaign

June 14 – October 17, 1777 at Upstate New York, Vermont

Campaign Summary

The Saratoga campaign was an attempt by the British high command for North America to gain military control of the strategically important Hudson River valley during the Revolutionary War. It ended in the surrender of the British army.

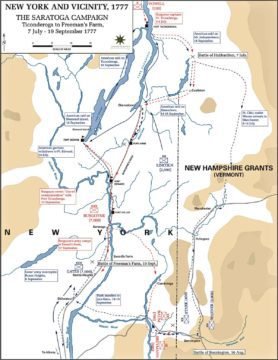

The primary thrust of the campaign was planned and initiated by Lieutenant General John Burgoyne. Commanding a main force of some 8,000 men, he moved south in June from Quebec, boated up Lake Champlain to middle New York, then marched over the divide and down the Hudson Valley to Saratoga. He initially skirmished there with the Patriot defenders with mixed results. Then, after losses in the Battles of Saratoga in September and October, his deteriorating position and ever increasing size of the American army forced him to surrender his forces to Brigadier General Horatio Gates on October 17.

The elaborate plans drawn up in London all failed. Colonel Barry St. Leger had been assigned to move east through the Mohawk River valley on Albany, New York, but was forced to retreat during the Siege of Fort Stanwix after losing his Indian allies. The major expedition from the south never materialized due to miscommunication with London when General William Howe sent his army to take Philadelphia rather than sending it up the Hudson River to coordinate with Burgoyne. A last-minute effort to reinforce Burgoyne from New York City was made in early October, but it was too little, too late.

The American victory was an enormous morale boost to the fledgling nation. More important, it convinced France to enter the war in alliance with America, openly providing money, soldiers, and munitions, as well as fighting a naval war worldwide against Britain.

Campaign Strategies

British Strategy

Toward the end of 1776, it was apparent to many in England that pacification of New England was very difficult due to the high concentration of Patriots; and so London decided to isolate New England and concentrate on the central and southern regions where Loyalists supposedly could be rallied.

In December 1776, Burgoyne met with Lord Germain, the British Secretary of State for the Colonies and the government official responsible for managing the war, to set strategy for 1777. There were two main armies in North America to work with: Major General Guy Carleton's army in Quebec and General William Howe's army, which had driven General George Washington's army from New York City in the New York and New Jersey campaign.

On November 30, 1776, Howe, the British commander-in-chief in North America, wrote to Germain, outlining an ambitious plan for the 1777 campaign. Howe said that if Germain sent him substantial reinforcements, he could launch multiple offensives, including sending 10,000 men up the Hudson River to take Albany, New York. Then, in the autumn, Howe could move south and capture the American capital of Philadelphia. Howe soon changed his mind after writing this letter: the reinforcements might not arrive, and the retreat of the Continental Army over the winter of 1776–77 made Philadelphia an increasingly vulnerable target. Therefore, Howe decided that he would make the capture of Philadelphia the primary object of the 1777 campaign. Howe sent Germain this revised plan, which Germain received on February 23, 1777.

Burgoyne, seeking to command a major force, proposed to isolate New England by an invasion from Quebec into New York. His invasion plan from Quebec had two components: he would lead the main force of about 8,000 men south from Montreal along Lake Champlain and the Hudson River Valley while a second column of about 2,000 men (which Barry St. Leger was chosen to lead), would move from Lake Ontario east down the Mohawk River valley in a strategic diversion.

Both expeditions would converge upon Albany, where they would link up with troops from Howe's army marching up the Hudson. Control of the Lake Champlain-Lake George-Hudson River route from Canada to New York City would cut off New England from the rest of the American colonies.

The last part of Burgoyne's proposal, the advance by Howe up the Hudson from New York City, proved to be the most controversial part of the campaign. Germain approved Burgoyne's plan after having received Howe's letter detailing his proposed offensive against Philadelphia.

In March 1777, Germain had approved of Howe's Philadelphia expedition and did not include any express orders for Howe to go to Albany. Yet Germain also sent Howe a copy of his instructions to Carleton which plainly stated that the northern army was to make a junction with Howe's army at Albany. In a letter from Germain to Howe dated May 18, 1777 he made clear that the Philadelphia expedition should "be executed in time for you to co-operate with the army ordered to proceed from Canada and put itself under your command." This last letter was not received by Howe until after he had departed New York for the Chesapeake.

To attack Philadelphia, Howe could either have moved overland through New Jersey or by sea via the Delaware Bay, both options would have kept him a position to aid Burgoyne if necessary. The final route he took, through the Chesapeake Bay, was immensely time-consuming and left him wholly unable to assist Burgoyne.

On May 6, Burgoyne returned to Quebec bearing a letter from Germain which introduced the plan but lacked some details. Burgoyne technically outranked Carleton, but Carleton was still the governor of Quebec. Germain's instructions to Burgoyne and Carleton had specifically limited Carleton's role to operations in Quebec.

American Strategy

Washington, whose army was encamped at Morristown, New Jersey, and the American military command, did not have a good picture of British plans for 1777. The principal question on the minds of Washington and his generals Gates and Major General Philip Schuyler was of the movements of Howe's army in New York.

They had no significant knowledge of what was being planned for the British forces in Quebec, in spite of Burgoyne's complaints that everyone in Montreal knew what he was planning. The three generals disagreed on what Burgoyne's most likely movement was, and Congress also rendered the opinion that Burgoyne's army was likely to move to New York by sea.

Partly as a result of this indecision, and the fact that it would be isolated from its supply lines if Howe moved north, the garrisons at Fort Ticonderoga and elsewhere in the Mohawk and Hudson valleys were not significantly increased. Schuyler took the measure in April 1777 of sending a large regiment under Colonel Peter Gansevoort to rehabilitate Fort Stanwix in the upper Mohawk valley as a step in defending against British movements in that area. Washington also ordered four regiments to be held at Peekskill, New York that could be directed either to the north or the south in response to British movements.

American troops were allocated throughout New York theater in June 1777. About 1,500 troops were in outposts along the Mohawk River, about 3,000 troops were in the Hudson River highlands under the command of Major General Israel Putnam, and Schuyler commanded about 4,000 troops (inclusive of local militia and the troops at Ticonderoga under St. Clair).

Campaign Begins

Most of Burgoyne's army had arrived in Quebec in the spring of 1776, and participated in the routing of Continental Army troops from the province. In addition to British regulars, the troops in Quebec included several regiments of Hessians, under the command of Major General Friedrich Adolph Riedesel. Of these regular forces, 200 British regulars and 300-400 Germans were assigned to St. Leger's Mohawk Valley expedition, and about 3,500 men remained in Quebec to protect the province.

The remaining forces were assigned to Burgoyne for the campaign to Albany. The regular forces were supposed to be augmented by as many as 2,000 militia raised in Quebec. By June, Carleton had managed to raise only three small companies. Burgoyne had also expected as many as 1,000 Indians to support the expedition. About 500 Indians joined between Montreal and Crown Point.

On June 13, Burgoyne and Carleton reviewed the assembled forces at St. John's on the Richelieu River, just north of Lake Champlain, and Burgoyne was ceremonially given command. In addition to five sailing ships built the previous year, a sixth had been built and three had been captured after the Battle of Valcour Island. These provided some transport as well as military cover for the large fleet of transport boats that moved the army south on the lake.

The army that Burgoyne launched the next day had about 7,000 regulars and over 130 artillery pieces. His regulars were organized into an advance force under Brigadier General Simon Fraser and two divisions. Major General William Phillips led the 3,900 British regulars on the right, while Riedesel's 3,100 Hessians held the left.

St. Leger's expedition was also assembled by mid-June. His force, a mixed company of British regulars, Loyalists, Hessians, and rangers from the Indian department, numbering about 750 men, left Lachine, near Montreal, on June 23.

Ticonderoga Falls

Burgoyne's army traveled up the lake and occupied the undefended Fort Crown Point by June 30. The screening activities of Burgoyne's Indian support were highly effective at keeping the Americans from learning the details of his movements. Brigadier General Arthur St. Clair, who had been left in command of Fort Ticonderoga and its surrounding defenses with a garrison of about 3,000 regulars and militia, had no idea on July 1 of the full strength of Burgoyne's army, large elements of which were then just 4 miles away. St. Clair had been ordered by Schuyler to hold out as long as possible, and had planned two avenues of retreat.

On July 2, open skirmishing began on the outer defense works of Ticonderoga. By July 4, most of the American garrison was either at Fort Ticonderoga or nearby Mount Independence. Unknown to the Americans, their withdrawal from an outer defensive position cleared a way for the British to place artillery on Sugar Loaf hilltop, whose heights commanded the fort.

On July 5, a second battle at Fort Ticonderoga occurred. The next day, Burgoyne's men occupied the main fortification and the positions on Mount Independence. The uncontested surrender of the supposedly impregnable fort caused a public and political uproar. This caused the Continental Congress to replace Schuyler with Gates as commander of the Northern Department of the Continental Army in August.

Burgoyne sent forces out from his main body to pursue the retreating army, which St. Clair had sent south via two different routes. The British caught up with elements of the retreating Americans at least three times. On July 7, Fraser and elements of Riedesel's troops faced determined resistance in Battle of Hubbardton and a skirmish at Skenesboro.

On July 8, these were followed by another standoff in the Battle of Fort Anne. These actions demonstrated to the British officers that the Americans were capable of putting up stiff resistance. Burgoyne's army was reduced by about 1,500 men as a result of the Ticonderoga actions. He left 400 men to garrison the magazine at Crown Point and another 900 to defend Ticonderoga. The bulk of St. Clair's army retreated through the New Hampshire Grants (present-day Vermont).

Reaction and Delay

On July 10, Burgoyne issued orders for the next series of movements. Most of the army was to take the rough road from Skenesboro to Fort Edward via Fort Anne, while the heavy artillery was to be transported down Lake George to Fort Edward. Riedesel's troops were sent back up the road toward Castleton, primarily as a diversion intended to suggest that he might be aiming for the Connecticut River.

Schuyler immediately rode to Fort Edward, where there was a garrison of about 700 regulars and 1,400 militia. He decided to make Burgoyne's passage as difficult as possible by chopping down and leaving large trees in the Burgoyne's path. This brought Burgoyne's advance to a crawl, tiring his troops and forcing them to use up supplies.

On July 11, Burgoyne wrote to Lord Germain, complaining that the Americans were systematically felling trees, destroying bridges, and damming streams along the road to Fort Edward. Schuyler also employed scorched earth tactics to deny the British access to local provisions. Schuyler's tactics required Burgoyne to build a road through the wilderness for his guns and troops, a task that took about two weeks.

On July 24, Burgoyne moved out of Skenesboro and reached Fort Edward five days later. He found that Schuyler had already abandoned it, in a retreat that ended at Stillwater, New York. Before he left Skenesboro, Burgoyne was joined by about 500 Indians from the Great Lakes region under the leadership of St. Luc de la Corne and Charles Michel de Langlade.

St. Leger's Expedition

St. Leger sailed up the St. Lawrence River and crossed Lake Ontario to arrive at Oswego. He had about 300 regulars, supported by 650 Canadian and Loyalist militia, and they were joined by 1,000 Indians led by John Butler and the Iroquois war chiefs Joseph Brant, Sayenqueraghta, and Cornplanter.

On July 25, they left Oswego and marched to Fort Stanwix on the Mohawk River. They began besieging Fort Stanwix on August 2. About 800 members of the Tryon County militia and their Indian allies marched to relieve the siege, but some of St. Leger's British and Indians ambushed them at the Battle of Oriskany.

On August 10, Brigadier General Benedict Arnold left Stillwater, New York for Fort Stanwix with 800 Continental regulars. He expected to recruit members of the Tryon County militia when he arrived at Fort Dayton. He could only raise about 100 militia. He staged the escape of a Loyalist captive, who convinced St. Leger that Arnold was coming with a much larger force than he actually had. On this news, Brant and the rest of St. Leger's Indians withdrew. St. Leger was forced to raise the siege and head back to Quebec.

The advance of Burgoyne's army to Fort Edward was preceded by a wave of Indians, which chased away the small contingent of troops left there by Schuyler. These allies became impatient and began indiscriminate raids on frontier families and settlements, which had the effect of increasing rather than reducing local support to the American rebels. In particular, the death at Indian hands of the young Loyalist settler Jane McCrea was widely publicized and served as a catalyst for rebel support, as Burgoyne's decision to not punish the perpetrators was seen as unwillingness or inability to keep the Indians under control.

On August 3, messengers from Howe finally succeeded in making their way through the American lines to Burgoyne's camp at Fort Edward. The messengers did not bring good news. On July 17, Howe wrote that he was preparing to depart by sea with his army to capture Philadelphia, and that Clinton, responsible for New York City's defense, would "act as occurrences may direct". Realizing that he now had a serious supply problem, Burgoyne decided to act on a suggestion that Riedesel had made to him in July. Riedesel observed that the area was rich in draft animals and horses, which might be seized for the army's benefit.

On August 9, pursuing this idea, Burgoyne sent Colonel Friedrich Baum's regiment toward western Massachusetts and the New Hampshire Grants, along with some Brunswick dragoons. Most of Baum's detachment never returned from the August 16 Battle of Bennington, and the reinforcements he had sent after them came back after they were ravaged in the same battle, which deprived Burgoyne of nearly 1,000 men and the much-needed supplies.

What Burgoyne had been unaware of was that St. Clair's calls for militia support following the withdrawal from Ticonderoga had been answered, and Brigadier General John Stark had placed 2,000 men at Bennington. Stark's force enveloped Baum's at Bennington, killing him and capturing much of his detachment.

On August 10, Congress sent Gates to take command of the Northern Department. It also ordered states from Pennsylvania to Massachusetts to call out their militias.

On August 19, Gates arrived at Albany to take charge. He was cold and arrogant in manner, and excluded Schuyler from his first war council. Schuyler left for Philadelphia shortly after, depriving Gates of his intimate knowledge of the area.

Throughout August and continuing into September, militia companies arrived at the Continental Army camps on the Hudson River. These were augmented by troops Washington ordered north from the Hudson Highlands as part of Arnold's operation to relieve Fort Stanwix. Those troops arrived at the end of August and included the sharpshooters of Daniel Morgan's rifle corps.

News of the American successes at Bennington and Fort Stanwix, combined with outrage over the death of Jane McCrea, rallied support, swelling Gates' army to over 6,000 rank and file. This number did not include Stark's small army at Bennington, but was also augmented by several hundred troops raised by Brigadier General Benjamin Lincoln, who was assigned to make attacks against Burgoyne's supply and communications.

Saratoga

The "Battle of Saratoga" is often depicted as a single event, but it was actually a month-long series of maneuvers punctuated by two battles. At the beginning of September 1777, Burgoyne's army was located on the east bank of the Hudson. He had learned of St. Leger's failure at Fort Stanwix, and even earlier that Howe would not be giving him substantial support. Faced with the need to reach defensible winter quarters, which would require either retreat back to Ticonderoga or advance to Albany, he decided on the latter. Subsequent to this decision, he made two further crucial decisions.

Burgoyne decided to deliberately cut communications to the north, so that he would not need to maintain a chain of heavily fortified outposts between his position and Ticonderoga, and he decided to cross the Hudson River while he was in a relatively strong position. He therefore ordered Riedesel, whose forces were in the rear, to abandon outposts from Skenesboro south, and ordered the army to cross the river just north of Saratoga, which it did between September 13-15.

Moving cautiously, since the departure of his Indian support had deprived him of reliable scouting, Burgoyne advanced to the south. On September 18, the vanguard of his army had reached a position just north of Saratoga, about 4 miles from the American defensive line, and skirmishes occurred between the leading elements of the armies.

On September 8, Gates ordered the army to Stillwater with the idea of setting up defenses there. The Polish engineer Brigadier General Tadeusz Kościuszko found the area inadequate for proper defensive works, so a new location was found about three miles further north (and about 10 miles south of Saratoga). At this location, Kosciusko laid out defensive lines stretching from the river to the bluffs called Bemis Heights. Gates assumed command of the army's right side himself. Gates put Arnold, with whom he had previously had a good relationship, in command of the army's left, the western defenses on Bemis Heights.

Freeman's Farm

Both Burgoyne and Arnold recognized the importance of the American left flank. Burgoyne recognized that the American position could be flanked, and divided his forces, sending a large detachment to the west on September 19. Arnold, also recognizing that a British attack on the left was likely, asked Gates for permission to move his forces out to Freeman's Farm to anticipate that maneuver.

Gates refused to carry out a general movement, since he wanted to wait behind his defenses for the expected frontal attack; but he did permit Arnold to send Colonel Daniel Morgan's riflemen and some light infantry out for a reconnaissance in force. These forces precipitated the Battle of Freeman's Farm when they made contact with Burgoyne's right flank. In the ensuing battle, the British gained control of Freeman's Farm, but with heavy casualties.

Burgoyne considered renewing the attack the next day, but called it off when Fraser noted that many men were fatigued from the previous day's exertions. He dug his army in and waited for news that he would receive some assistance from the south. Although he was aware of the persistent desertions that were reducing the size of his army and that the army was running short of food and other critical supplies, he did not know that the American army was also daily growing in size, or that Gates had intelligence on how dire the situation was in his camp.

Attack on Ticonderoga

Unknown to either side at Saratoga until after the battle, Lincoln and Colonel John Brown had staged an attack against the British position at Fort Ticonderoga. Lincoln sent three detachments of 500 men each to "annoy, divide, and distract the enemy." One went to Skenesboro, which was found to be abandoned by the British. The second went to capture Mount Independence on the east side of Lake Champlain, while the third, led by Brown, made the approach to Ticonderoga.

On the morning of September 18, Brown surprised the British defenders at the southern end of the portage trail connecting Lake George to Lake Champlain. Rapidly moving up the trail, his men continued to surprise British defenders and capture artillery pieces until they reached the height of land just before Ticonderoga, where they occupied the "old French lines".

On the way, he rescued 100 American prisoners and captured nearly 300 British. His demand for the fort's surrender was refused, and for the next four days, Brown's men and the fort exchanged cannon fire, to little effect. Since he had insufficient manpower to actually assault the fort, Brown then withdrew to Lake George, where he made an unsuccessful attempt to capture a storage depot on an island in the lake.

Gates wrote to Lincoln on the day of Freeman's Farm, ordering his force back to Saratoga. Lincoln reached Bemis Heights on September 22, but the last of his troops did not arrive until September 29.

Howe, when he left New York for Philadelphia, had put General Henry Clinton in charge of New York's defense, with instructions to assist Burgoyne if opportunities arose. Clinton wrote to Burgoyne on September 12 that he would "make a push at [Fort] Montgomery in about ten days" if "you think 2000 men can assist you effectually."

On October 3, Clinton sailed up the Hudson River with 3,000 men, and three days later, captured Forts Clinton and Montgomery. Burgoyne never received Clinton's dispatches following this victory, as all three messengers were captured. Clinton followed up the victory by dismantling the chain across the Hudson River, and sent a raiding force up the river. Word of Clinton's movements only reached Gates after the battle of Bemis Heights.

Bemis Heights

In addition to Lincoln's 2,000 men, militia units poured into the American camp, swelling the American army to over 15,000 men. Burgoyne, who had put his army on short rations on October 3, called a council the next day. The decision of this meeting was to launch a reconnaissance in force of about 1,700 men toward the American left flank.

On October 7, Burgoyne and Fraser led this detachment out early in the afternoon. Their movements were spotted, and Gates wanted to order only Morgan's men out in opposition. Arnold said that this was clearly insufficient, and that a large force had to be sent.

Gates, put off one last time by Arnold's tone, dismissed him, saying, "You have no business here." However, Gates did accede to similar advice given by Lincoln. In addition to sending Morgan's company around the British right, he also sent Colonel Enoch Poor's brigade against Burgoyne's left. When Poor's men made contact, the Battle of Bemis Heights was underway.

The initial American attack was highly effective, and Burgoyne attempted to order a withdrawal, but his aide was shot down before the order could be broadcast. In intense fighting, the flanks of Burgoyne's force were exposed, while the Hessians at the center held against Learned's determined attack. Fraser was mortally wounded in this phase of the battle. After Fraser's fall and the arrival of additional American troops, Burgoyne ordered what was left of his force to retreat behind their entrenched lines.

Arnold, frustrated by the sound of fighting he was not involved in, rode off from the American headquarters to join the battle. Arnold took the fight to the British position. The right side of the British line consisted of two earthen redoubts that had been erected on Freeman's Farm.

Arnold first rallied troops to attack Balcarres' redoubt, without success. He then rode through the gap between the two redoubts, a space guarded by a small company of Canadian irregulars. Learned's men followed, and made an assault on the open rear of Breymann's redoubt. Arnold's horse was shot out from under him, pinning him and breaking his leg. Breymann was killed in the action, and his position was taken. However, night was falling, and the battle came to an end. The battle was a bloodbath for Burgoyne's troops.

Surrender

Fraser died of his wounds early the next day, but it was not until nearly sunset that he was buried. Burgoyne then ordered the army, whose entrenchments had been subjected to persistent harassment by the Americans, to retreat.

It took the army nearly two days to reach Saratoga, in which heavy rain and American probes against the column slowed the army's pace. Burgoyne was aided by logistical problems in the American camp, where the army's ability to move forward was hampered by delays in bringing forward and issuing rations. However, Gates did order detachments to take positions on the east side of the Hudson to oppose any attempted crossings.

By the morning of October 13, Burgoyne's army was completely surrounded, so his council voted to open negotiations. Terms were agreed on October 16 that Burgoyne insisted on calling a "convention" rather than a capitulation.

On October 17, following a ceremony in which Burgoyne gave his sword to Gates, only to have it returned, Burgoyne's army marched out to surrender their arms while the American musicians played "Yankee Doodle".

Aftermath

British troops withdrew from Ticonderoga and Crown Point in November, and Lake Champlain was free of British troops by early December. American troops, on the other hand, still had work to do. Alerted to Clinton's raids on the Hudson, most of the army marched south toward Albany on October 18, while other detachments accompanied the "Convention Army" east. Burgoyne and Riedesel became guests of Schuyler, who had come north from Albany to witness the surrender.

Burgoyne was allowed to return to England on parole in May 1778, where he spent the next two years defending his actions in Parliament and the press. He was eventually exchanged for more than 1,000 American prisoners.

In response to Burgoyne's surrender, Congress declared December 18, 1777 as a national day "for solemn Thanksgiving and praise" in recognition of the military success at Saratoga; it was the nation's first official observance of a holiday with that name.

Under the terms of the convention, Burgoyne's army was to march to Boston, where British ships would transport it back to England, on condition that its members not participate in the conflict until they were formally exchanged. Congress demanded that Burgoyne provide a list of troops in the army so that the terms of the agreement concerning future combat could be enforced. When he refused, Congress decided not to honor the terms of the convention, and the army remained in captivity.

The army was kept for some time in sparse camps throughout New England. Although individual officers were exchanged, much of the "Convention Army" was eventually marched south to Virginia, where it remained prisoner for several years. Throughout its captivity, a large number of men (more than 1,300 in the first year alone) escaped and effectively deserted, settling in the United States.

On December 4, word reached Benjamin Franklin at Versailles that Philadelphia had fallen and that Burgoyne had surrendered. Two days later, King Louis XVI assented to negotiations for an alliance.The treaty was signed on February 6, 1778, and France declared war on Britain one month later, with hostilities beginning with naval skirmishes off Ushant in June.

Spain did not enter into the war until 1779, when it entered the war as an ally of France pursuant to the secret Treaty of Aranjuez. Vergennes' diplomatic moves following the French entry into the war also had material impact on the later entry of the Dutch Republic into the war, and declarations of neutrality on the part of other important geopolitical players like Russia.

The British government of Lord North came under sharp criticism when the news of Burgoyne's surrender reached London. Of Lord Germain, it was said that "the secretary is incapable of conducting a war", and Horace Walpole opined (incorrectly, as it turned out) that "we are ... very near the end of the American war." Lord North issued a proposal for peace terms in Parliament that did not include independence; when these were finally delivered to Congress by the Carlisle Peace Commission, they were rejected.